Feyisa Demie is an Honorary Fellow at Durham University and head of research for school self-evaluation at Lambeth Local Authority. In this post he summarises his research paper that breaks down linguistic background data and attainment in Key Stage 2 SATs for children classed broadly as ‘Eastern European’ in English schools. In the light of the recent government scrapping of the English proficiency scales, Feyisa’s analysis provides a timely reminder of the importance of data collection around linguistic proficiency if policy and practice are to address educational inequality effectively.

Background

English schools have been educating immigrant children for decades. Recently, however, there has been a sizeable growth of immigrant population in the UK. Research conducted by the Migration Policy Institute suggests that the immigrant population as whole increased from 4.9 million to 8.6 million between 2002 and 2015 (a relative increase of 76%). Of these, 3.1 million were European citizens, 1.3 million of whom hailed from Eastern Europe. Naturally, this increase in the general population was accompanied by an increase in the school population. Of the nearly 6.7 million pupils in English schools nearly 120,000 (or 1.8%) came from Eastern European countries.

Despite the prominence of East Europeans in the fabric of British society, very little research evidence or national data pertaining to the educational achievement and experiences among this group exists. This places serious constraints on informing policy and practice at national and local levels to ensure that this group are being well served by the education system.

The study summarised in this blog post examined differences in pupil performance among the most common Eastern European languages represented in English schools. It draws on detailed National Pupil Database (NPD) and School Census data for pupils who completed Key Stage 2 (KS2) in England in 2016.

Eastern European Languages in English Primary Schools

The bar chart below indicates the diversity of Eastern European languages spoken by children in English schools. The largest group by some distance are speakers of Polish (53,915 speakers). Speakers of Albanian, Lithuanian and Russian, form the next largest groups, then commensurately smaller numbers of speakers of the 24 different Eastern European languages recorded in the NPD.

The 2016 Key Stage 2 SAT results of the 18,340 pupils in this diverse group of learners were analysed in relation to the different languages represented among it, and compared to the results of pupils from other linguistic groups.

Findings

The table below shows that, taken as a whole, speakers of Eastern European languages tended to do less well in their Key Stage 2 SATs than children in other linguistic groups. Overall 41% speakers of Eastern European languages gained the expected standard in reading, writing and maths combined. This compares with 48% of speakers of Western European languages (excluding English) and 53% of all pupils nationally. The biggest difference in SAT scores was in reading, where 66% of all pupils met the expected standard nationally, while only 48% of speakers of Eastern European languages did.

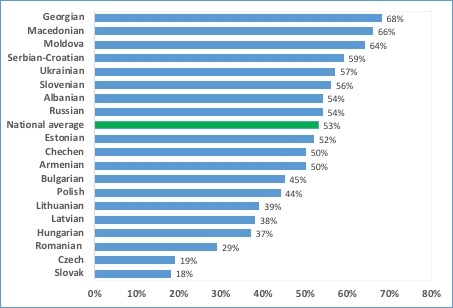

However, when the figure for Eastern European languages as a whole is disaggregated, a more nuanced picture emerges. The bar chart below shows that within the Eastern European languages group, Georgian speaking pupils were the highest achieving with 68% reaching expected levels. They were closely followed by speakers of Macedonian (66%), Romanian (64%), and Serbian (61%). Lower on the scale, but still above the national average, were speakers of Ukrainian (57%), Slovenian (56%), Russian (54%), and Albanian (54%).

In contrast, a number of Eastern European groups fall well below the national average. Speakers of Slovakian were by far the lowest performing, with just 18% achieving expected levels at Key Stage 2. With speakers of Czech (19%), they are amongst the lowest performing language groups across the country, with a gap of over 44 percentage points below the national average. This is a much bigger gap than suggested by the average figure for Eastern Europeans as a whole. Other low attaining Eastern European linguistic groups were speakers of Romanian (30%), Latvian (38%), Hungarian (37%), Lithuanian (39%), Polish (44%), Bulgarian (45%) and Estonian (52%).

So, while speakers of Eastern European languages are often considered an underachieving group in general, clearly this is an insufficiently instructive interpretation of the empirical reality.

Conclusions and policy implications for data collection

The main findings from the study confirm that a significant number of Eastern European pupils have low attainment on high-stakes national assessments and that this underachievement is an issue that policymakers and schools must address. However, to consider Eastern Europeans as a homogenous group is unhelpful, as certain linguistic groups within that larger population are tending to do very well at school.

The other important finding of this study has implications for the collection and use of data at national and international levels. I would argue that the worryingly low achievement of some Eastern European pupils has been masked by the failure to distinguish other important demographic characteristics of children classified as White Other (the most common classification used by Eastern Europeans) in government statistics. Using such categories as they are collected at the national level in England can have undesirable consequences for policy formulation. Accurate and reliable disaggregated ethnic and language data are clearly important to address education inequalities. I would argue as a matter of good practice, government and public institutions need to account for people’s culture, ethnic and linguistic background in formulating national and local policy.

This post is a summary of Language diversity and educational attainment of East European pupils in primary schools in England, a paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association (BERA), University of Sussex, 6th September 2017.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.