This is a guest post by Mirela Dumić, a teacher of Croatian at the International School of London, in Surrey. Mirela and her students created a bilingual short film (at the end of this post) that was shown at the British Film Institute in London. In this post she describes the process and the lessons she and her multilingual learners took away.

Our participation in a digital multilingual storytelling project run by Goldsmiths (University of London) and the British Film Institute gave my Croatian pupils aged 8-12 a unique opportunity to bring a famous Croatian fairy tale to a wider audience in the form of a bilingual shadow puppet film. Under the project’s umbrella theme of ‘fairness’, the pupils created their own adaptation of the fairy tale Stribor’s Forest (Šuma Striborova) by famous Croatian writer Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić.

In this blog I would like to share our journey which may serve as a resource for a similar classroom project which draws on a classic story from a national culture, and provides a shared space for a mother tongue and EAL.

A story chosen to tell: Stribor’s Forest

In Croatia all children grow up with Stribor’s Forest. Over generations the story has inspired both adults and children to give it a new life in film, animation, illustration and theatre productions, so the engagement with this classic literary piece has never abated. With all that in mind the reason for our choice was obvious. The writer’s sources of inspiration, her original plots, vivid characters and universal themes make it an attractive choice for adaptations. This year also marks 100 years since it was published in 1916 so there was one more reason to bring it to a new audience.

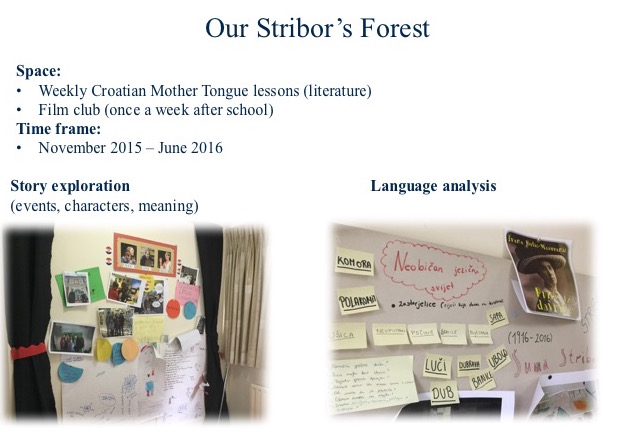

Project space: Croatian Mother Tongue lessons and film club

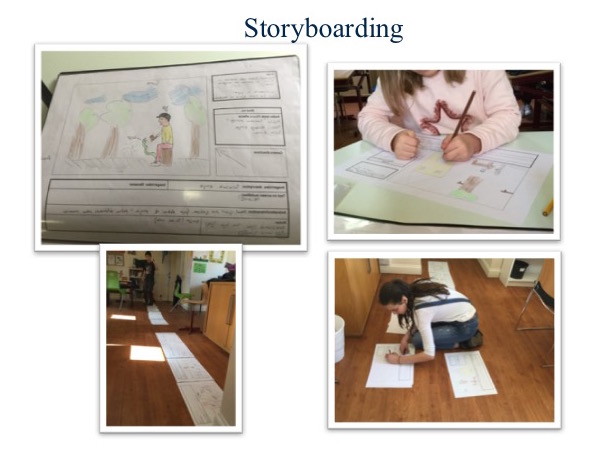

Integrating the film project within our literature lessons and leaving the practical part for a weekly after school film club with our art teacher and myself was a convenient, meaningful and productive set up. Bringing the characters to life in our film club after analysing the story and producing storyboards in our lessons was a very enjoyable and engaging disciplinary transition for my pupils.

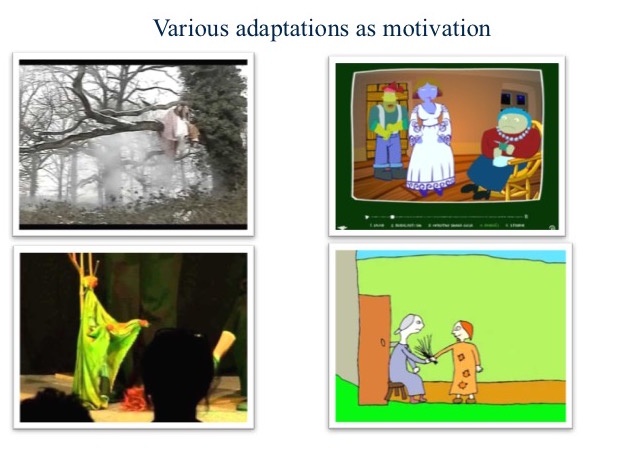

Watching and commenting the story’s adaptations

Watching various short adaptations of Stribor’s Forest in Croatian and commenting on different aspects (choice of scenes, characters, language adaptation, scenery) and discovering differences between the original story and a particular adaptation was a very engaging activity. The pupils also wrote short reviews. This overall activity certainly spurred their motivation to create their own version.

What to include and in what kind of language?

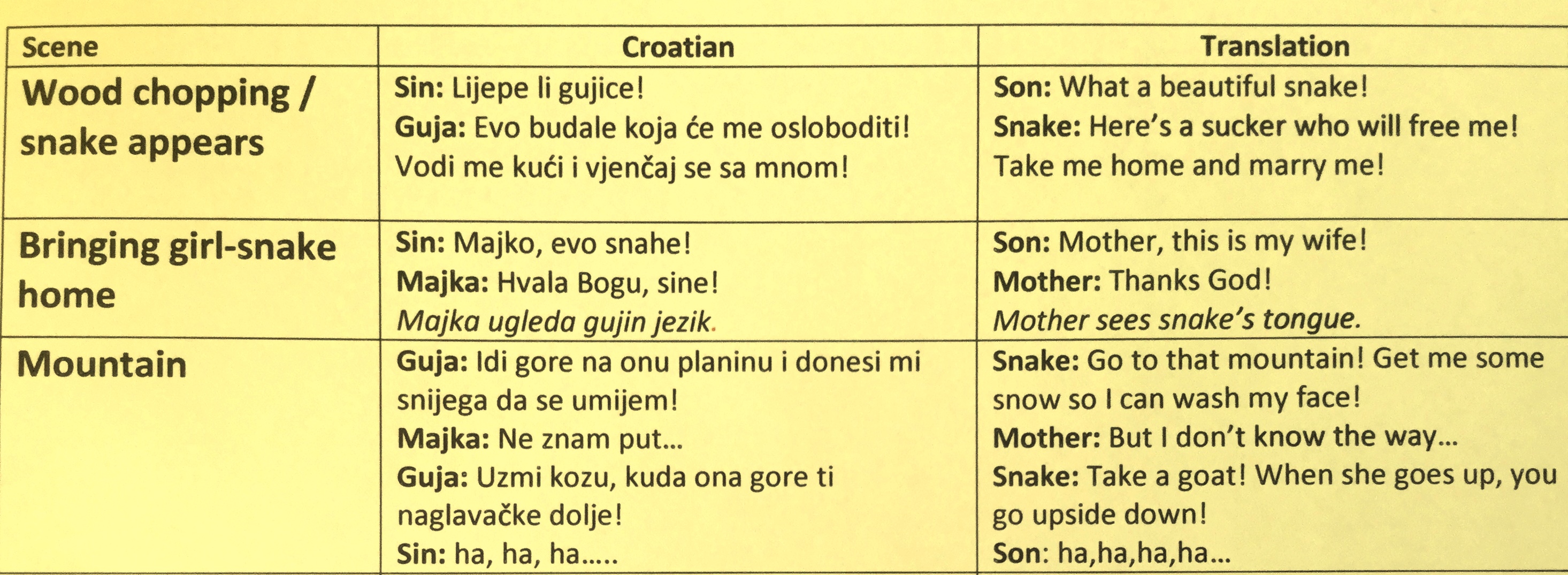

This was a tricky and rewarding step. The pupils quickly realised that an adaptation also meant sacrificing parts of a story and perhaps ‘throwing away’ your favourite bits. We had to keep in mind that we had only five minutes of film space and we had to collaborate! Discussions about what to leave in and what to leave out, while still retaining the spirit of the story, resulted in a creative language exercise with parts of the story given poetic twists with a rhyme.

The ‘musical’ language in the original story, its ‘old’ words and archaic expressions whose meaning we discussed in our lessons, were given a ‘special treatment’ after some hesitation. Rather than discarding them as irrelevant and ‘too old’ as they observed initially, the pupils engaged with the writer’s language at a deeper level during the storyboarding activity and naturally gravitated towards some expressions used by the writer. They thought it was cool!

Let’s do it now in English!

This was a novelty in our lessons. Interacting with my pupils exclusively in Croatian for almost two years, I was pleasantly surprised by their enthusiasm to translate the story lines into English. For the first time the two languages met in their lesson in a very creative way. For me personally it was a revelation to see how much their English had developed (they arrived in the UK with very little English). Whether to use ‘a fool’ or ‘a sucker’, whether to translate a rhyme and whether to translate a line or rely on visual clues instead were some of the discussions we indulged in. According to them this was a very challenging and rewarding task on our film journey.

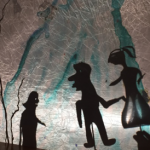

Acting out the story: bringing languages and art together

The pupils wanted anonymity and ‘something different’ for their film to stand out. They were up for the challenge and they liked the idea of shadow puppetry mentioned by our art and design teacher. This interdisciplinary collaboration has immensely enriched the experience of both the pupils and the teachers, and contributed greatly to the whole project. So much creativity happened in this interaction!

Insights about shadow puppetry:

- Paper cutting is very forgiving. The shadow is the only thing that counts. The puppet can be ripped, repaired altered, and no-one will ever see mistakes.

- Behind the screen the students have their own zone. They are separated from the teachers and audience, so they have complete independence and anonymity but must work together!

- Shadows can be experimented with. There is a transformation that occurs as the shadow is much bigger and darker than the student. This is quite a powerful medium to be playing with and quite empowering for the student.

Many thanks to Marc Smith, Art and Design teacher at ISL Surrey, for these insights.

Putting it all in one film

Our ‘classroom made’ sound effects (so much fun!), recorded narration (done separately after filming) and our editing skills (we used Movie Maker and iMovies) finally brought our film to life. It was shown at the BFI in London as part of the project’s film awards ceremony and also at our school during a Folk Tales night. We are all very proud of our achievement. Enjoy watching the film below!

Resources

Critical Connections II Project

Handbook for Teachers (creating a multilingual digital story, a step-by-step guide)

Stribor’s Forest in English (page 161)

Contact

Mirela Dumić, Croatian Mother Tongue Teacher, International School of London (Surrey)

mdumic@islsurrey.org