I had the good fortune to be in Melbourne at the end of November and visited the fantastic Immigration Museum, which just so happened to be having a special exhibition about British migrants to Australia. It was illuminating to be put in the position of the migrant rather than migrant-watcher for a change. Skilled workers were in short supply in post-war Australia and so campaigns like this one aimed at teachers were launched to tempt vitamin D challenged Brits to come over and fill the gap. It worked. Between 1947 and 1981, 1.5 million Brits migrated to Australia. There was the ‘£10 Pom’ assisted passage migration scheme to help people who would otherwise have been unable to afford to make the move.

One of the prime motives for this scheme was a deliberate attempt to ensure a predominantly white Australia. As John Curtin, the Australian Prime Minister in put it in 1941, ‘This nation will remain forever the home of sons of Britishers who came here in peace to establish an outpost of the British race. Our laws have proclaimed the standard of a white Australia … we intend to keep it, because we know it to be desirable.’ You wouldn’t find a mainstream politician expressing their racist attitudes quite so openly these days, but that doesn’t mean similar ideologies don’t underpin some of our current policies with the economic hurdles put in the way of would-be migrants and English language tests that inevitably favour some groups over others. Still, lesson one, Brits aren’t always ‘ex-pats’ – they can be economic migrants too!

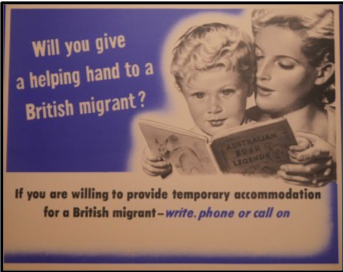

The exhibition charted the stories of several individuals and families, looking at their reasons for migrating, the difficulties they faced with housing, jobs and settling in. Housing was an enormous issue and thousands of people found themselves living in temporary accommodation – barracks, essentially – until they were able to be moved on. There was a government drive to help out with temporary housing and people offering a spare room to needy British migrants. We’ve seen recent similar initiatives here to help refugees, mainly through religious organisations rather than the state, but I wonder whether a government drive like the one shown above would be imaginable in Britain these days.

The exhibition charted the stories of several individuals and families, looking at their reasons for migrating, the difficulties they faced with housing, jobs and settling in. Housing was an enormous issue and thousands of people found themselves living in temporary accommodation – barracks, essentially – until they were able to be moved on. There was a government drive to help out with temporary housing and people offering a spare room to needy British migrants. We’ve seen recent similar initiatives here to help refugees, mainly through religious organisations rather than the state, but I wonder whether a government drive like the one shown above would be imaginable in Britain these days.

Post-war Britain needed to attract migrants too, of course. The Attlee Labour Government of 1945 oversaw a massive expanse in public services such as the newly founded NHS. When we see the constant drip-drip-drip of toxic anti-migrant headlines from the Daily Mail these days, it may seem hard to imagine that seventy years ago the British press was offering a similarly warm welcome to the so-called Windrush Generation with front-covers such as this one from the Evening Standard (right) on June 21, 1948, the day before the ship’s arrival in the ‘Motherland’, as journalist Denise Richards put it, beneath the headline ‘Welcome Home!’. Of course, homes actually turned out to be somewhat harder to come by as the sons and daughters of Empire soon discovered.

Post-war Britain needed to attract migrants too, of course. The Attlee Labour Government of 1945 oversaw a massive expanse in public services such as the newly founded NHS. When we see the constant drip-drip-drip of toxic anti-migrant headlines from the Daily Mail these days, it may seem hard to imagine that seventy years ago the British press was offering a similarly warm welcome to the so-called Windrush Generation with front-covers such as this one from the Evening Standard (right) on June 21, 1948, the day before the ship’s arrival in the ‘Motherland’, as journalist Denise Richards put it, beneath the headline ‘Welcome Home!’. Of course, homes actually turned out to be somewhat harder to come by as the sons and daughters of Empire soon discovered.

I wouldn’t want to give the impression that all was sunny in Australia, either. A series of acts passed in 1901 effectively instituted a ‘whites-only’ policy. From a linguist’s point of view, one of the most outrageous features of the legislative powers was the institution of the dictation test. Would-be entrants to the country could be asked to take down a circa 50 word dictation in any European language the immigration officer chose. If they passed the test the officer was at liberty to make them do it over and over again, in a different language each time until they failed it.

One notorious example of this truly ‘high-stakes’ test was that of the Czech, Jewish, communist, Egon Kisch. The saga of Kisch’s attempts to take up an invitation from left wing Australian groups to visit Australia in 1934 to warn about the perils of fascism is a salutary reminder of the power of language in the hands of the state. The authorities were not keen to have him land and so they used the immigration act to thwart his efforts to disembark in Perth and he was forced to stay on board whilst the ship sailed on to Melbourne. Here, Kisch decided to take matters into his own hands (or feet) and he literally jumped ship – a six-metre drop – breaking his leg in the process. Rather than being taken to hospital. He was carried back on board and the ship sailed on to Sydney where he won a habeas corpus hearing and on leaving the ship he was escorted to a nearby police station where he was invited to write down the words of The Lord’s Prayer recited to him in Scottish Gaelic by a certain Constable McKay. Whilst fluent in several European languages, Kisch was forced to decline the invitation and so was barred from entry. Much legal wrangling ensued. Ultimately, Constable McKay’s linguistic competence was called into doubt when he was asked to translate a sentence of Scottish Gaelic for the court. He duly rendered it as, ‘As well as we could benefit, and if we let her scatter free to the bad’ and pointed out that it was ‘not a very moral sentence’, only to discover that the more usual translation was ‘Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil’ –the closing words of The Lord’s Prayer. Kisch’s lawyers went on to argue that Scottish Gaelic was not, in fact, a European language and this was upheld by the High Court. This in turn led to angry letters to the Sydney Morning Herald from no less an authority than the Chancellor of Sydney University, Sir Mungo MacCallum who castigated the courts, declaring:

‘Some of us may have supposed the Immigration Act was meant to provide a test whereby, even if in a quibbling and pettifogging way, undesirable aliens might be excluded … Now we know better. It behoves us to bow down before the court’s confident pronouncement: ‘We are dictators over all language and above linguistic facts.’’

Kisch was eventually released on bail while further habeas corpus hearings continued and eventually, a fudge was reached with Kisch being allowed to stay for six months after which he voluntarily left the country. Despite this case illustrating the discriminatory (and frankly farcical) nature of the dictation test, it was not finally abandoned until 1958. We may feel that our English language tests, administered solely in Standard English, are a beacon of enlightenment in comparison. Having said that, in 2016, when the UK government announced tighter restrictions on entry, including a language test, The Independent challenged its readers with some sample questions and asked them to comment on how well they did. Their readers were not slow to point out problems with some of the questions, including:

2. Have you finished with the newspaper…

…already?

…still?

…now?

…yet?

At least three of those might be considered acceptable, and one reader, much concerned with rules relating to the use of the comma and defining relative clauses, objected strenuously to:

7. Choose the correct missing word, ‘The invited us to dinner … was very nice of them.’

…which

…that

And, of course, this leaves aside the other test for British citizenship, which includes questions I must admit to getting wrong myself, such as

When did the Boxer Rebellion war start?

1894

1896

1899

Or how about this one:

When was the Giant’s Causeway formed?

20 million years ago

40 million years ago

60 million years ago

I was in very good company with an unsurprisingly large percentage of my fellow The Evening Standard test-takers, but I did get the question about Jane Austen’s birthplace right, which is something.

The exhibition posed an interesting question which, given the mongrel pedigree of the British, we might all want to ponder, ‘When do you stop being a migrant and start being Australian?’. It seems those earlier proponents of a white Australia were happy to imagine that a land literally the other side of the world could be inherently British merely by them being there. How is it that we now imagine when others come to these shores they are forever ‘other’? Well at least, if they don’t know the date of the Boxer Rebellion. (Spoiler alert, it was 1899, and it had nothing to do with men’s underwear.)

Frank Monaghan is Senior Lecturer in Applied Linguistics at the Open University and co-opted member of NALDIC’s executive committee.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.