Doctoral researcher Denise Amankwah shares with NALDIC her work and some important reflections on African heritage languages

Doctoral researcher Denise Amankwah shares with NALDIC her work and some important reflections on African heritage languages

Prior to embarking on my PhD journey, I was working as a speech and language advisor with many different schools and nurseries in highly multilingual London boroughs. The most fascinating part of this role was observing how particular groups of languages beyond English were treated, recognised, and used by parents, students and teachers.

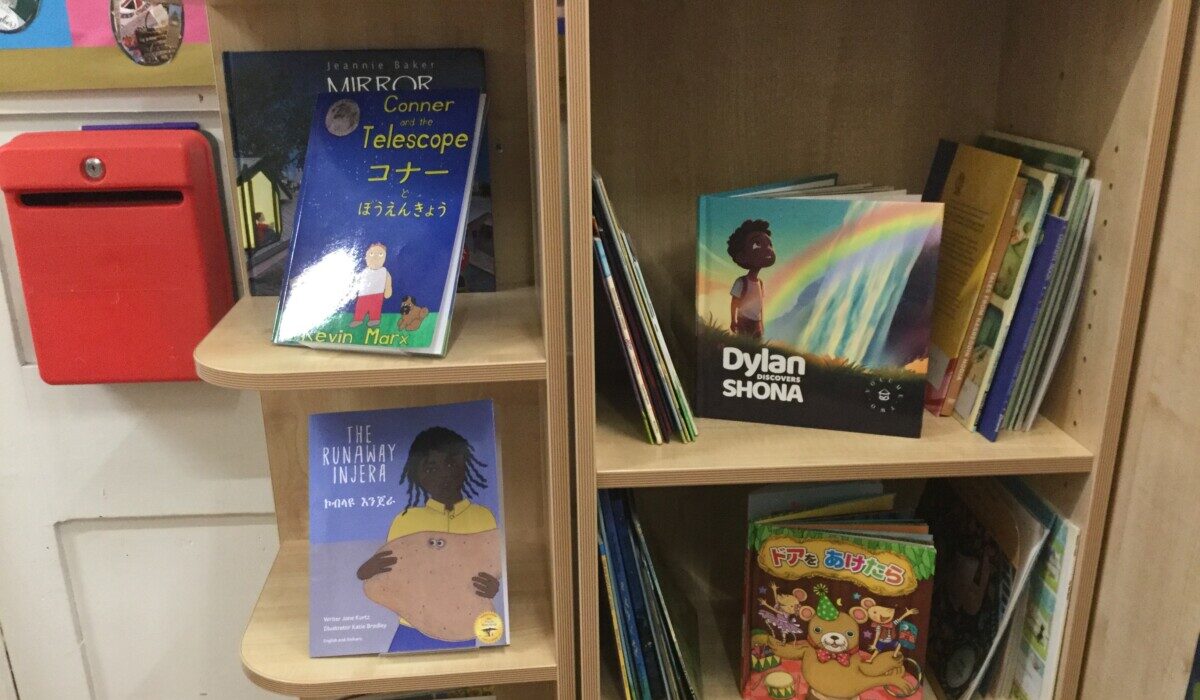

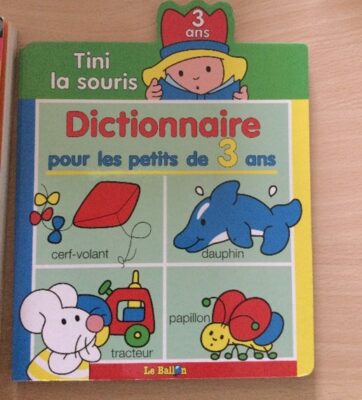

One borough, in particular, really pushed positive messaging regarding bilingualism to all staff. Educators would proudly share their research-backed knowledge during our training days saying, “It’s great if parents speak their home language!” or “Bilingualism is an asset”. Their pro-bilingualism ethos was noticeable even without these interactions as pupils’ languages were often displayed around their classrooms. Here are some examples:

Despite this beautiful linguistic representation, I could not help but notice that African languages, in particular Sub-Saharan ones, were often less represented across these settings. What truly struck me was that this lack of visibility occurred even in settings where pupils of Black African descent were the clear ethnic majority!

Being Black (British) African myself and having experienced heritage language loss after I began attending nursery in the UK, I started to consider what covert and overt messages are transmitted about African languages in educational settings. Are African languages overtly valued, or do they tend to be ignored? Are these languages as well-resourced as other pupils’ languages? What knowledge, if any, do teachers hold about African languages? Do African parents feel strongly for, indifferently or against their children developing fluency in African languages? I am exploring these matters currently in my doctoral research, but I also touched on some of these questions in my Master’s dissertation which is now a published paper.

In this study, I interviewed both London-based Early Years educators and African parents living in London regarding their language attitudes and practices. I found that most of the parents attributed little value towards African languages and their ideologies appeared to be remnants of colonial thinking (Amankwah & Howard, 2024). Parents also shared the punishments they faced at school for speaking their native language instead of the (European) colonial language – I argued that this also shaped their thoughts on their native language(s). Even on the African continent today, there is evidence of parents actively choosing not to pass down their native language but rather adopting the former colonial language as their home language (Afrifa et al., 2019).

My research indicates that parents are aware of linguistic hierarchies. It is therefore very important for educators to be clear in promoting the value of all languages, especially for parents who have migrated from countries that were once colonised as they may carry colonial language ideologies. When these conversations do not happen, this could contribute to linguistic invisibility.

My doctoral journey so far has shown that:

- Children of African migrants tend to regret having lost fluency in their (African) heritage language.

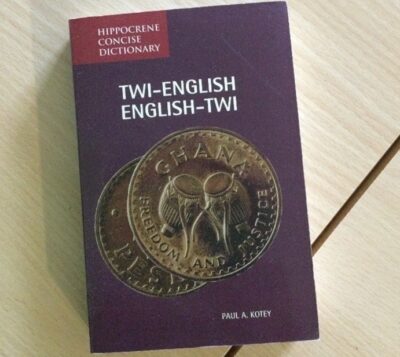

- The number of complementary schools for African languages in the UK is very limited and high-quality bilingual books in African languages are difficult to find.

- Many of the participants in my study would greatly benefit from access to research on race, colonialism, and language, and how these are interconnected

In Ọlátúnjí’s (2023) exploration of a specific African language group (Yoruba) in London, she found that the first-generation Yoruba parents in her study did not transmit Yoruba to their children as they did not identify any value in doing so. However, Ọlátúnjí (2023) recognised that there has been a recent attitudinal shift. In my current doctoral study, I have captured wonderful examples of more inclusive linguistic representation.

Next steps

Talking about it is already taking action! Welply (2022)discusses the need for EAL provision and practice to be decolonised and for educators to critically reflect on their current ideas around linguistic inclusion. I hope that research like this continue to shed light on African (and other minoritised) languages in the UK, revealing how educators can help increase their visibility and positively support parents to keep their family languages alive.

Here’s a little first step. I have developed a survey to paint a more detailed picture of the language practices and ideologies that exist amongst families who speak African languages in the UK. If you know of a parent/carer of African descent living in the UK, please share the QR code below with them to support this research and help us bring awareness:

References

Afrifa, G. A., Anderson, J. A., & Ansah, G. N. (2019). The choice of English as a home language in urban Ghana. Current Issues in Language Planning, 20(4), 418–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2019.1582947

Amankwah, D., & Howard, K. (2024). “English on a pedestal”: the language attitudes and practices of African migrant bilingual parents and early years professionals in the U.K. English in Education, 58(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/04250494.2024.2310660

Ọlátúnjí, Adékúnmi (2023) ‘Reflections on how Family Language Policies have contributed to language shift among Yorùbás in London.’ SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics, 21. pp. 64-82 https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/40384/1/FINAL_SWPL21_Olatunji.pdf

Welply, O. (2022). English as an additional language (EAL): Decolonising provision and practice. The Curriculum Journal, 34(1), 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.182

Find out more about multilingualism

Find out more about multilingualism

- Join one of our Regional or Special Interest Groups

- Attend one of our free NALDIC events this year

- Do you have a story to share? Write a post for the NALDIC blog