Hannah M. King and Gonzalo Pérez Andrade, researchers and lecturers at the London Metropolitan University, share with NALDIC their experience of creating a mobile multilingual library of picture books

In 2022, we started a research project that asks what impact a school-university partnership can have on multilingual awareness across an educator-student-community triad. In doing so, we connected our university with a primary school in the East London Borough of Newham, a highly diverse area where around 73% of students are considered EAL (Department for Education, 2020). Despite the school’s multilingual profile and growing awareness of it, we were surprised by the lack of non-English language books on their bookshelves. Similarly, the local public library only had children’s books in English.

In response, we decided to create (and we continue to grow!) a mobile, multilingual library of picture books. In the beginning, we targeted languages that were representative of our partner school’s context, and since, we have started extending its reach to other educational, academic, and public settings. You can follow the project on Twitter/X: @MultilingLondon.

Why do we need multilingual libraries?

Despite positive changes such as an increasing acknowledgement of non-English languages in English primary schools (Cunningham & Little, 2022) and further awareness of multilingual repertoires (Martínez, 2018), parents, communities, and institutions still regularly prioritise the English language and English language literacy at the expense of home languages. This raises questions about if, when, and where pupils’ languages are acknowledged, because if not, how could they feel represented?

We know that representation matters, as the visibility of one’s language impacts whether people see their language(s) recognised as ‘normal’ (Gorter et al., 2019) or not. Picture books specifically have been linked to inclusive pedagogies (Garces-Bacsal et al., 2022) and social justice, as they have the power to “counter inequitable cultural hegemony” (Daly & Kelly-Ware, 2022, p.1) and thus challenge the status quo. Also, picture books are for everyone! They can be adapted and applied to myriad topics and language levels, enjoyed alone or in community, and ‘read’ by anyone since children and adults alike can use illustrations to creatively imagine their own stories – in any language(s).

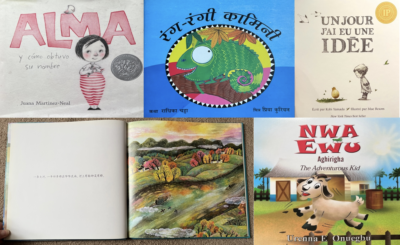

Some picture books from our collection, clockwise, from top left: Alma y cómo obtuvo su nombre (Alma and How She Got Her Name, Spanish), रंग-बिरंगी कामिनी (Colour-Colour Kamini, Hindi), Un Jour J’ai Eu Une Idée (What Do You Do With an Idea?, French), Nwa Ewu Aghịrịgha (The Adventurous Kid, Igbo and English), a page from 条大鱼向东游 (The Wooden Fish, Simplified Chinese)

Getting started

Starting a multilingual library might feel intimidating. You might ask: Which languages should be represented? How can I source books in languages I can’t read or understand myself? How can their quality be assessed? Should I choose dual-language, original, or translated books? It can seem difficult, but these perceived challenges can be overcome through collaboration, adaptability, and creativity!

For us, a library is ‘multilingual’ when it houses books in a variety of different languages, but the details depend on your community’s needs and desires. To create our library, for example, we started from what we knew about the linguistic repertoires of the school’s students and selected picture books which could be representative. We also tried to diversify them in terms of imagery, stories, cultural content, and authors; ultimately building a library of 110 books in 44 languages (and counting!). It takes time, but it is possible. Here are examples of how similar libraries were developed in Oxford and in Sheffield.

Just gathering books is not enough

So, you have a beautiful shelf of books in different languages. Now what? As part of our initiative, we organised an after-school literacy programme, a ‘Multilingual Story Time’, which brought together university student volunteers and pupils to read picture books together in various languages. We observed students (re)connecting with their home or heritage languages and displaying linguistic skills, with students not only reading in languages they knew, but also engaging with stories in their peers’ languages.

Another recent event showcasing the books was our Pop-up Multilingual Library at London Metropolitan University, which brought together local schools and libraries as well as London Met students and staff.

Concluding reflections

Although it may feel like a big step, developing a multilingual library can be relatively simple and affordable. Don’t be afraid to ask for help and work collaboratively. Educators, librarians, students, and others have helped us overcome challenges with accessing resources. Here you can find a Padlet to share resources. As for funds, remember that a few books is all it takes to get started. At the end of the day, representation matters! By creating multilingual libraries, we can increase the visibility of minority and home languages while raising awareness of the value of multilingual literacy. Ask yourself when and where the languages of your students and community are visible and if it is not yet in the form of a multilingual library, what are you waiting for?

References

Cunningham, C., & Little, S. (2022). ‘Inert benevolence’ towards languages beyond English in the discourses of English primary school teachers. Linguistics and Education, 78, 101-122.

Daly, N., & Kelly-Ware, J. (2022). Striving for social justice: The power that picturebooks have to counter inequitable cultural hegemony. Waikato Journal of Education, 27(1), 1-4.

Department for Education (2020). English proficiency of pupils with English as an additional language. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-proficiency-pupils-with-english-as-additional-language.

Garces-Bacsal, R. M., Akhosani, N. M., Elhoweris, H., Al Ghufli, H. T., AlOwais, N., Baja, E. S. & Tupas, R. (2022). Using diverse picturebooks for inclusive practices and transformative pedagogies. In M. Efstratopoulou (Ed.), Rethinking Inclusion and Transformation in Special Education. IGI Global. (72-92).

Gorter, D., Marten, H. F., & Van Mensel, L. (2019). Linguistic landscapes and minority languages. In G. Hogan-Brun & B. O’Rourke (Eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Minority Languages and Communities. Palgrave Macmillan. (481-506)

Do you have a story to share?

- Join one of our Regional or Special Interest Groups

- Attend one of our free NALDIC events this year

- Write a post for the NALDIC blog –get in touch