Mirela Dumić and Clare Brumpton set up a ‘Research Institute’ at their school, working with early-teen students to investigate issues around multilingualism. A report of the students’ work was published in the Autumn 2017 issue of the EAL Journal. Here, they share their own insights for colleagues who might want to set up similar projects.

Let them bring their language experience into research

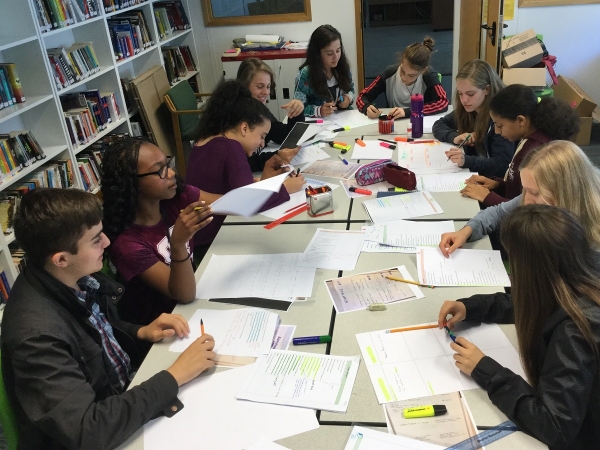

Like many other schools, the International School of London (Surrey) has a diverse student population at different stages of English proficiency, so ‘multilingualism’ as an umbrella theme was a very appropriate topic for our students to investigate. The school also promotes students’ first languages through a Mother Tongue Programme. Consequently, this research project presented an opportunity which would bring students’ languages to the fore and allow them to contribute as experts in their own linguistic experiences. Above all, this inspired them to come up with a research question that mattered to them: Do the languages that a multilingual student in an international school is exposed to affect the languages they think in?

We used the following activities to come up with a research question:

My language story

We asked students to brainstorm their language experience in pairs (mind mapping) and write a personal language journey to share with others in the group. We discovered that students needed a bit of convincing that their language experience matters, is unique, and could inform the research process. To facilitate the activity, we also reflected on our own language stories and shared them with our pupils. Having a visitor with multilingual experience during this session gave our students further impetus to share their own.

“In my lifetime, I have experienced French, Spanish, German, Chinese, Japanese, Braille, British Sign Language, Norwegian, Arabic and Yoruba. I’m technically monolingual, since I only speak English fluently, but I can hold a conversation and read quite a bit in around 4 of these languages.”

The following study activities which encourage linguistic self-reflection come from Colin Baker’s book, ‘Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism’.

My language timeline

We asked our students to illustrate how their bi/multilingual ability and language use has developed and changed since birth. This gave ‘at a glance’ history of our students’ language development, changes, contexts and countries over time. We used a horizontal arrow, but you can also use diagrams and tables.

Language interviews

This activity prompted linguistic self-discovery and was done in pairs. Being an interviewer/interviewee in this exercise also prepared students for semi-structured interviews in their data collection. The responses to the following questions were shared with the group at the end:

Group discussion: What is bilingualism/multilingualism?

Bringing insights from the previous exercises into a group discussion on the definition of bilingualism /multilingualism provided a platform for a vigorous debate. Initially, students seemed to agree that someone can call themselves bi/multilingual only if both languages are ‘perfect’, but they soon realised that there is no straightforward definition!

Linking personal experience with the research literature

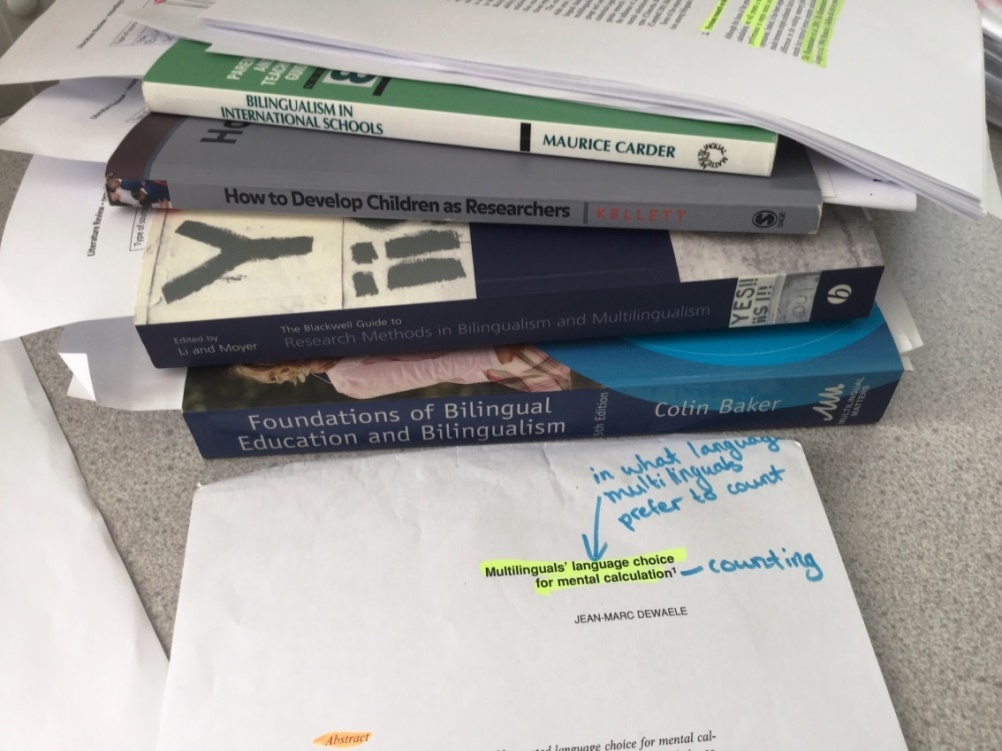

Scaffolding the literature review process for this age group presented a methodological challenge which required careful planning of literature sources and approaches to analysis. Given the available timeframe we limited the number of sources to a manageable number. The main purpose was to familiarise students with this step in the research process and different sources of literature.

Scaffolding literature in three steps:

- Personal language stories.

A book of narratives by multilingual students in an international school (book by Maurice Carder) provided context, with various language experiences that our students could identify with. They highlighted common themes, compared them and discussed them in pairs. This was a good preparation for interview coding during qualitative analysis!

- Blogs by academic scholars

This was students’ first encounter with theoretical explanations and related research studies. The blogs’ accessible writing style, engaging examples from research studies and their short format made them a very popular reading among our students. We used blogs by leading scholars in the field of language and thinking (e.g. by Pavlenko and Grosjean).

- Academic articles

We had a go! An article about mental calculation and language by Dewaele was a topic they could identify with. They managed to engage with research questions, methodology, findings (compared them to their experience), and learned how an article is structured.

We also produced a literature card which contained main details about each publication for referencing.

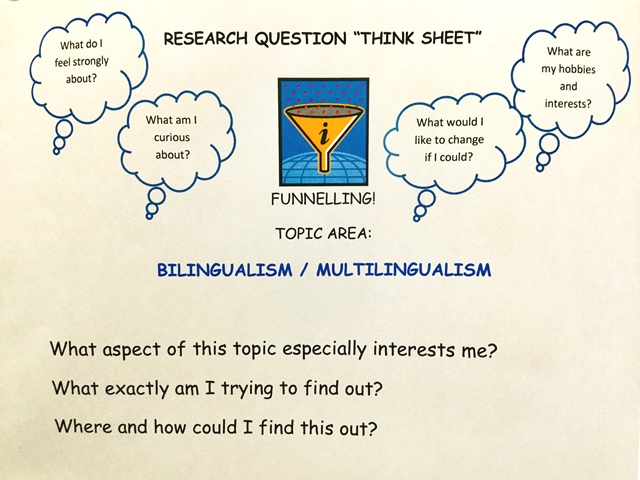

Crafting a research question using a Think Sheet

We gave each student a ‘Think Sheet’ to funnel their ideas, come up with questions they would like to explore and suggest how, where and by whom their question could be answered. This was done individually and the ideas were shared within the group. The final question was decided through a voting process.

Designing a questionnaire and interviews

Keeping in mind that their question had to be answerable and doable within the time-frame we had, the students’ suggested designing a questionnaire, a format they were familiar with as respondents. As for participants, they targeted secondary students in their own and another international school where they could get easy access. However, they started to see the benefits of drafting, re-drafting and piloting stages (improved questionnaire) as we were moving on. Using an existing questionnaire from a similar study as a model gave them an insight into the construction of questionnaire topics, question types and response scales (e.g. Likert scale). We used Survey Monkey to administer the questionnaire (see final Questionnaire in the Report).

Students realised that some questions would benefit from more in-depth responses which would better inform their study so they designed an interview guide with topics they wanted explore in semi-structured interviews.

Give them research skills to lead

Students were given training focusing on different aspects of research:

- What is research? Why is it important?

- The ethics of research. How to carry out ethical research / be an ethical researcher (consent forms, right to withdraw, etc.)

- How to design methodology around the research question

- How to design a survey (including piloting and redrafting)

- How to design a semi-structured interview (including piloting and creating an interview guide)

- Analysing findings (coding interviews and basic statistical analysis)

- Write up for dissemination

Throughout the process we used Mary Kellet’s book ‘How to Develop Children as Researchers: A Step by Step Guide to Teaching the Research Process’ as an invaluable resource with age appropriate methodological approaches, research study activities and examples.

These sessions were led by us and on several occasions by our academic mentor whose contribution and engagement was very much appreciated by our students.

Findings, analysis and write up

Both stages were driven by students’ strengths and interests (each pair focused on a particular section of analysis / report writing). During write up, students started linking and making connections between their own language experiences, the literature they had read and their findings. A report writing frame (structure, content, voice) was a very useful starting point for the writing process. As students started picking up academic language during the literature review this was an opportunity to introduce it in their own writing, with our support and guidance. If we could do this project again we are sure that our students would have designed a shorter questionnaire – they had too much data, they realised! For Findings and Discussion see the Report.

Final thoughts

A project like this provides an excellent platform for collaborations between students and teachers across the school (two of our teachers were part of the Ethics Panel). Time and energy is required to make this happen and both staff and students need to be open to allowing the time away from ‘curriculum’ activities for it to grow and develop. The project itself is flexible, scalable and adaptable depending on the classroom context and available time. Finally, as we said at the beginning, what inspired us to write this blog are students’ insights about this research experience.

See more in this video:

Project links

Video with students’ reflections.

Background to the project

This pilot research project at the International School of London (Surrey) was launched as part of a wider school’s initiative, a Research Institute which would give Grade 8 and 9 students (aged 13-14) the opportunity to conduct original research, develop academic skills and engage in collaborative interdisciplinary work. This research project took six months with weekly research sessions.

Recommended resources

- Kellett’s book “How to Develop Children as Researchers: A Step by Step Guide to Teaching the Research Process”

We highly recommend the Children’s Research Centre’s website (based at Open University) if you decide to develop a research project with your pupils

A short synopsis of research training for children is available here

Examples of research by children and young people

Academic paper Children as Researchers in English Primary Schools: Developing a Model for Good Practice by Sue Bucknall.

The EAL Journal is published termly by NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.