Jenny Verney is an English teacher and EAL and Academic Literacy Coordinator at a secondary school in Sheffield. She teaches GCSE English and A-Level English Language, and writes and delivers courses in Academic English. In this blog post she discusses the joys and challenges of developing a curriculum to teach academic language.

It was early 2011. I had recently returned from one Maternity Leave and, due to a lack of planning equal to many a teenage pregnancy, was about to go on another. I was working part-time, juggling teaching and child care. The Deputy Head, with an admirable lack of concern about my capacity to commit to a new project (for which I will be forever grateful!), had given me the go-ahead to pilot a new course called Academic English.

This course, which had a different focus than traditional English teaching (see below), came about through a deep frustration that we weren’t equipping our advanced EAL learners with the skills they needed to really succeed at GCSE, A Level and beyond. Yes, many would get grades that enabled them to move into Sixth Form, college and apprenticeships, but others would just miss out, even though, cognitively, we knew they were able. Some would get into Sixth Form, pass their A Level courses by dint of sheer hard work, but would come out at the end with grades that didn’t do justice to their motivation, stamina and bright, bright ideas. What finally spurred me into action was a wonderful group of girls who studied English Language A Level with me in 2009. Articulate, funny and with a sophisticated bilingual, bicultural understanding of the world, these women are now teachers and product designers. They did well, got their target grades. But they could have done even better. The barrier was their written expression, and by Year 13 it was too late. We needed to give explicit instruction in how to use academic English and we needed to start earlier.

| English | Academic English |

| Gives equal weighting to the skills of Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening (supposedly). | Predominantly focuses on Writing. |

| Teaches students to write in different voices and style – poetry, fictional prose, diaries and so on. | Main focus is to teach students to write in one voice – the impersonal academic voice. |

| Encourages creativity with fictional writing – expression of emotions. | Is equally creative but is more about the expression of complex ideas – critical thinking. |

| Students study fiction and non-fiction in depth. | Students study short, non-fiction texts. The texts are used as the springboard for ideas. |

The differences between an English and Academic English focus

Much of my frustration came from the knowledge that there was a wealth of materials and a developed pedagogy already out there. In the summers of 2005 and 2006, during a break from Secondary work, I had great fun teaching EAP (English for Academic Purposes) at Durham University. The point of EAP is to make explicit the conventions of academic language in English to international students who are already fluent. The course was tightly focused on the magic three – academic vocabulary, grammar and text structure – and was exactly what our students needed at Secondary level. But when I returned to Secondary teaching and rang around publishers asking for EAP materials suitable for teenagers in the UK, I hit a wall. Despite EAP being a huge cash-cow at tertiary level, there seemed to be little awareness that it might be relevant to the mainstream Secondary market.

Lacking the materials to proceed, we set about writing our own EAP course. Excited discussion between the Deputy Head and I ensued and we bashed out the principles and practicalities of the course. It would begin in Year 8, be cross-curricular and have a grammar focus for each unit. We would teach the structure and generic conventions of different types of academic text. Students would learn to use a wide range of academic vocabulary. There would be an insistence on a piece of extended, redrafted writing for each unit. The course would offer a ‘window on the world’ through high-quality reading materials, such as articles from the New Scientist and broadsheets. We would never shy away from difficult words or concepts, but we’d have the time to break them down and discuss them.

As is the way when you’ve been mulling over an idea for a long time, the outline of the course was easy to write. The Year 9 curriculum looked like this, and has changed very little in the years since I wrote it.

| Topic title/project and linked subject | Grammar point | Academic Skills | Written outcome |

| Top chef

>Food Technology

|

Modals

Can, could, may, might, must, will, would, shall, should. |

Reading for understanding and inference. Use of Style Models. | Recipe following the generic conventions of celebrity chefs’ writing. |

| Life on Mars

>Science |

Passive voice – future

Will be built/Will be grown |

Deconstructing a text; précis and summary. | Discursive essay – Should Humans Live on Mars? (Fishbone) |

| Tourism and eco-tourism

> Geography |

Using adverbial phrases at the start of sentences (“Culturally,…) | Fishbone planning – independent application | Discursive essay – Is tourism a force for good of does it perpetuate inequality? (Fishbone) |

| Disaster! News reporting

> English |

Reporting verbs

Described; Stated; Said. Tense usage. |

Deconstructing genre; synthesis | TV news – report recounting eye witness stories. |

| Moral Dilemmas

> PSHE/RE |

Conditional usage | The language and structure of argument | Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis essay about a moral dilemma |

Year 9 Academic English curriculum

We were inspired and guided by the work of several people. The first was Dr Lynne Cameron and her 2003 OFSTED research into writing at secondary level.[i] Like my students, the participants were advanced EAL learners, many of whom had been born in the UK, and the research highlighted the importance of explicit instruction in academic writing skills. One paragraph really caught my attention – a school had identified fourteen areas of difficulty in the writing of their advanced EAL students:

comparatives and superlatives; idiom; spelling; possessives and apostrophes; capital letters; prepositions; countables and uncountables; pronouns; vocabulary; direct and reported speech; subject/verb agreement; passive voice; case; and tenses.

(Cameron, 2003, HMI 1102 p. 15)

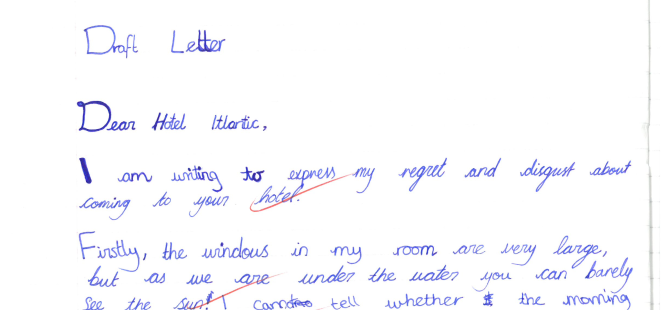

Needing a structure with which to plot the grammar component, this list became the go-to guide for my planning and I integrated most of the areas into the Academic English curriculum. So, for example, in Year 8, we looked at using conditional sentence structures when writing a letter of complaint to a hotel:

In Year 9, we aimed to widen our use of tenses when writing a news report about a natural disaster. This is an example of teacher-led group writing:

If I am being completely honest, the grammar teaching on the course was probably the least inspiring part (for me and the students!). There was so much exciting content to discuss – 20th Century dictators, the impact of tourism on local water supplies, Pliny and Vesuvius, the ethics of human colonisation of Mars – that the grammar instruction tended towards the dry and prescriptive. Any suggestions for imaginative grammar teaching gratefully received …

A second influence was the work of Manny Vazquez on developing a wide and academic vocabulary. I had heard Manny talk a number of times in Sheffield, and his insistence that students’ achievement is inextricably linked to vocabulary size chimed so clearly with what I was seeing in the classroom. His article ‘Beyond Key Words, or … was the dodo a sitting duck?’ (NALDIC Quarterly) gave me a philosophy and a practical approach to teaching vocabulary. In it, Manny argues that we need to be prepared to step outside our subject when discussing vocabulary – that simply giving out lists of Key Words is too limiting. His solution is clear:

a much more and broader sustained approach to vocabulary development whereby all teachers approach their planning with a commitment to developing deep word knowledge and have an understanding that often, students may well be taking a meaning literally and not metaphorically.

This commitment to exploring meaning and avoiding assumptions about students’ understanding became a key component of the Academic English approach. Every text was scrutinised for new vocabulary and metaphorical meaning. We had regular spellings and definitions tests. Students became very competitive over who was the quickest with the dictionary!

Armed with this mix of EAP pedagogy, grammar focus and vocabulary extension, we piloted the course in 2011 with a small group of bilingual students. We quickly realised that grammar and vocabulary were important but that our young people also needed support in other academic areas – organising their writing, avoiding plagiarism, effective research and revision techniques. Five years on, and the course has evolved to meet these areas of need. But nothing stays the same. As of this month, Academic English has become ARCC (Academic Register, Cultural Capital) and teaches History, Geography and RE through the prism of academic literacy. It’s the start of a new journey – a very exciting, challenging and rewarding one. But that’s a story for another day.

[i] Writing in English as an Additional Language at Key Stage 4 and post-16 and More advanced learners of English as an additional language in secondary schools and colleges