Dr. Daniel Semakula is medical doctor at the Makerere University College of Health Sciences in Uganda, and Allen Nsangi is a Doctoral Researcher at Oslo University in Norway. They were recently involved in a large research project with Ugandan school children on critical thinking about health claims. Uganda, like all African countries, enjoys complex linguistic diversity. The official language of education is English, yet children speak any one (or more) of more than 40 indigenous languages at home. In this post, Daniel and Allen describe how they accounted for the linguistic diversity of the children and adults in their study. This included involving local people in the design of the programme, and drawing on local languages to support teaching in English.

In many parts of the world health claims are often accepted uncritically. In the West, some people believe that vaccines cause autism, despite no evidence that this is true. In Uganda, one of many common claims about treatments is that applying cow dung to skin burns makes them heal faster. When people accept claims like these uncritically they can put themselves at risk of harm. Unfortunately, many people do not have the understanding and skills needed to assess the trustworthiness of such claims, and therefore to make informed choices. To address this, we developed a programme to teach these skills to Ugandan primary school children and their parents.

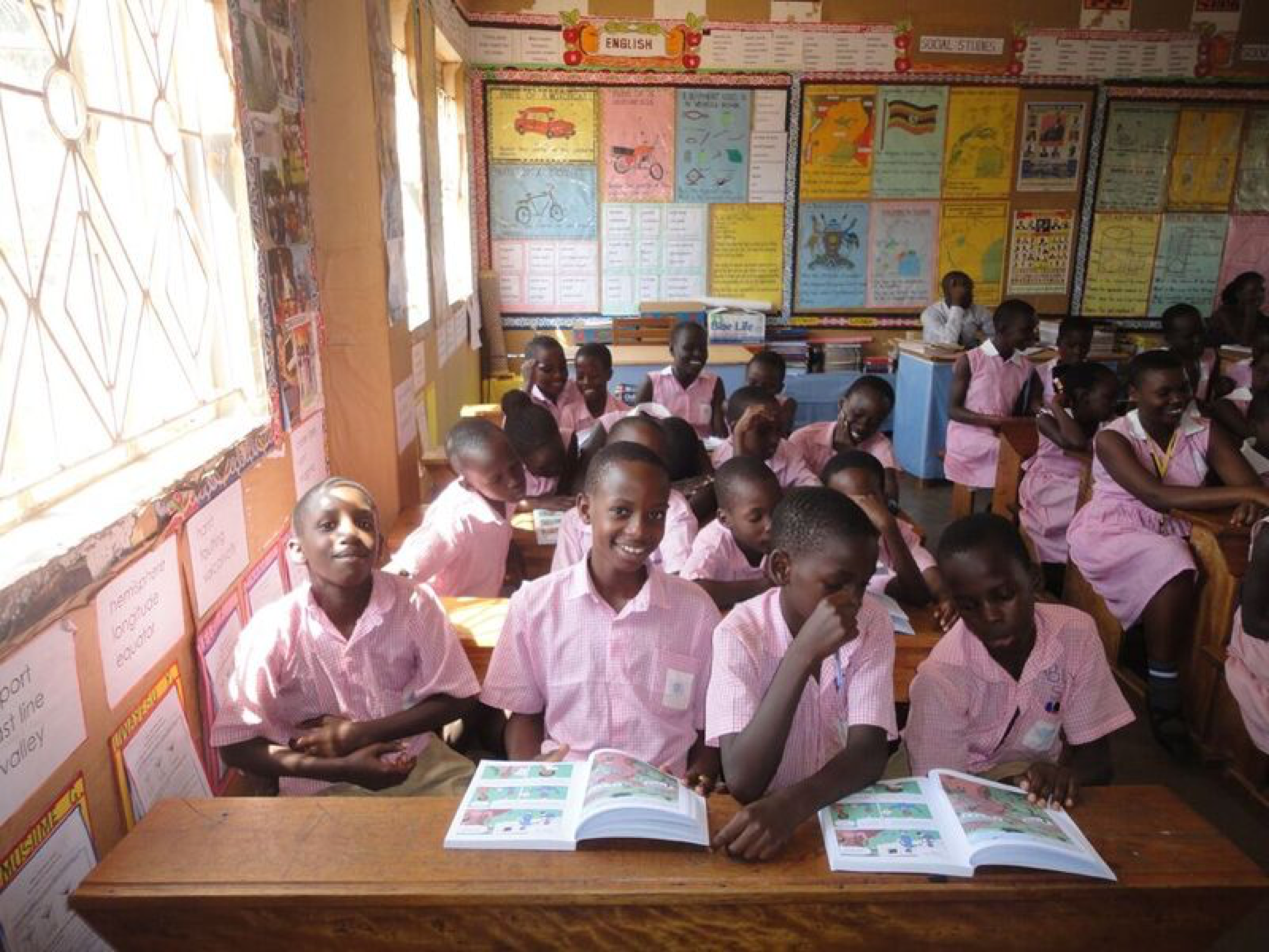

The programme was delivered in government schools in central Uganda where the language of instruction is English, but where most children speak Luganda as a first language. The main teaching resources were a children’s comic book and a podcast for their parents. These resources illustrated and explained ‘Key Concepts’ that are needed to assess the trustworthiness of health claims. Our challenge was to develop these materials so that they were appropriate for our multi-ethnic and multi-lingual setting. In particular we faced five language challenges.

Our first challenge related to the use of English as the official language. The education system in Uganda emphasizes English as the official medium of instruction. However, English is a second language to most. The majority of people have problems understanding and using English.

The second challenge related to the use of scientific terms in English. Some of the language of science does not have directly relatable equivalent words in plain English. An example from our study was randomized trial. Trial, to mean experimental comparison, is easily confused with trials as in the courts of law, and trials as in frustrating attempts.

The third challenge was that there was often no direct local equivalent for many English scientific terms. These included, for example, anecdote, chance, and unfair. It was extremely difficult to find words or short phrases in local languages that could be used to explain these kinds of concept.

The fourth challenge concerned the demographics of the study area. The predominant local language is Luganda. However, the area is populated with speakers of a mix of many other languages. This meant that we had to consider other languages used by minority groups living in the study area, not just the first language of the majority. In addition, while classes were typically extremely linguistically diverse, the teachers could usually speak only two or three languages – English, the local language, and their own first language (if different from the local language).

The fifth challenge was in response to government policy. We were expected to accommodate Kiswahili, a language that has recently been commissioned as Uganda’s second official language, but which very few people in our study area and the country at large speak.

Each of these five challenges not only made teaching the ‘Key Concepts’ difficult but also presented problems in choosing alternative languages and approaches. Overall the process required careful consideration of the scientific, linguistic, ethical, political and cultural implications of all the possible options.

To overcome these technical bottlenecks, we sought the advice of teachers, journalists, parents and children, through networks we had established earlier in the project. Using their counsel, we decided to translate the difficult words to the most commonly spoken language in the study area, which was Luganda. Whereas it made practical sense to translate into Luganda, we also included translations into Kiswahili. Although not many people speak Kiswahili, it and English are the two official languages acceptable to government. It made political sense to include it. We were aware that even with the inclusion of two additional languages in the comic book, speakers of other languages would feel disenfranchised. So, we left a large space next to the Luganda and Kiswahili translations so that we or the users could add other languages if needed.

Pages from the comic book with translations of key terms. Click to enlarge

When we user-tested the comic book with the translations, we noted that the children were able to understand the new terms we had planned to teach them. The teachers too were pleased, because the materials were acceptable and relevant. Similarly with the podcast, we translated all 13 English episodes to Luganda. We found that even when people were proficient in English, they often preferred to listen to the episodes in Luganda and to complete the follow-up questionnaire in Luganda too. It was also interesting to note that the written version of the Luganda questionnaire was not sufficient to aid engagement because many people were not literate in Luganda. We therefore also audio-recorded the questionnaire using Luganda.

While we were delivering the programme, we frequently observed that children had difficulty expressing their understanding of scientific concepts in English. We were concerned that this might mean their understanding would be misrepresented in the final assessment, which was conducted in English. In the event, we took a random sample of children and asked them to complete the test translated into Luganda and administered as a pre-recorded audio questionnaire. The results showed that children demonstrated their understanding better in Luganda compared to English.

We are not language specialists, but we noticed that there seems to be potential for conflict in the way languages are used in education in Uganda. It is important that children are fluent in English, which is both an official medium of instruction and an examinable subject, but at the same time we want to ensure that they understand the content of what they are taught in school. In fact, we noticed that the teachers often switched to a local language if they noticed that English was hindering learning. In the project, our concern was that children understood what claims are, and the ‘Key Concepts’ necessary for assessing their trustworthiness. Therefore, we catered for the use of multiple languages.

The project was a great success. Children in our programme demonstrated knowledge of the skills needed to assess the trustworthiness of health claims. We feel that using Luganda was an important contribution to the programme’s success, and recognize the wider implications of teaching children in a language other than their first.

To learn more about the Informed Health Choices project visit its website http://www.informedhealthchoices.org

This post is based on research published in Nsangi, A., Semakula, D., et al. (2017). Effects of the Informed Health Choices primary school intervention on the ability of children in Uganda to assess the reliability of claims about treatment effects: a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, Vol 390 No 10092 p374-388.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.