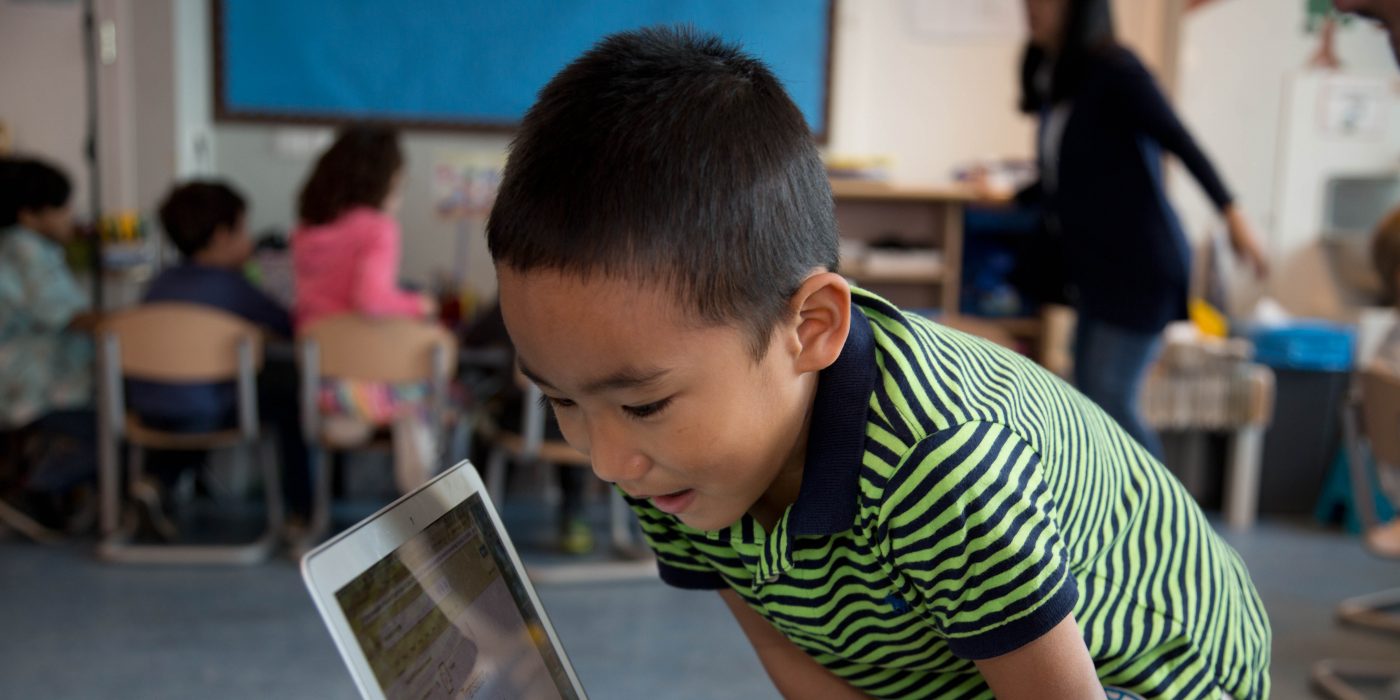

Using children’s home languages in English medium classrooms is widely agreed to be good practice. But how can teachers with classes with lots of different home languages make this a reality for all children? Josh Martin and Mindy McCracken of the International School of the Hague describe their innovative approach using Google translate for just this purpose.

The International School of the Hague (ISH) Primary, where we work, is host to ninety-plus nationalities and over sixty different languages. This means approximately eighty percent of the school’s student population is bilingual. Since 2011, the ISH has been implementing a trial translanguaging approach across both EAL and mainstream teaching contexts. In Key Stage 2, this approach is based on integrating the use of Google translate for scaffolding literacy and curriculum content. Written translations give students the ability to express academic and linguistic knowledge that is still well beyond their reach in English. In this vein, we wanted to explore how similar strategies might operate in Key stage 1 and Foundation Stage classrooms, where oral language use predominates. This article therefore follows an ongoing Year 1 translanguaging trial, where 5-6 year old English beginners make use of Google speaker buttons to facilitate their social and academic learning.

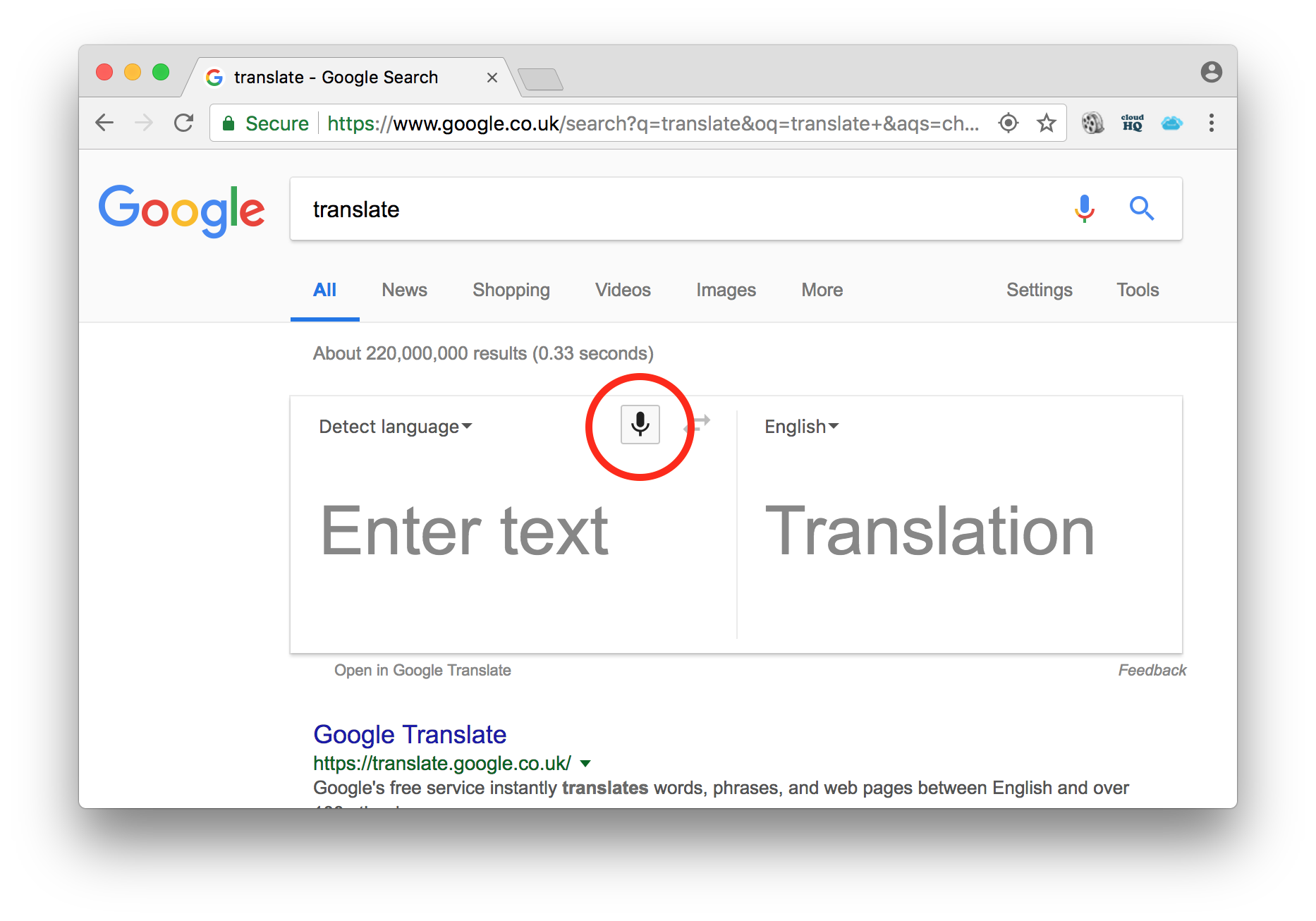

Speaker buttons are a simple feature of the Google Chrome internet browser. Using the computer’s microphone, the Google Translate interface allows you speak or type in one language and have that translated into any one of huge number of different languages, and hear the translation as audio. Initially, they allow EAL students to express their basic needs and wants. Being able to communicate feelings and describe situations to their teachers and peers is an enormous boon to a child’s comfort and well being in school. It also enables the teacher to set up peer-to-peer communication between students, allowing them to share ideas and resolve conflicts far sooner than would normally be possible.

Imagine that a child wishes to build a shop in the classroom, and if others wish to enter, they need to get a special ticket. With the use of a speaker button, the child can communicate this plan to the rest of the class by speaking into a laptop which is connected to an interactive whiteboard. Sharing a child’s home language in this prominent place likewise elevates its status as a valid language for learning.

As the students in the classroom become more familiar with the presence of speaker buttons, they recognize that they can be used to communicate with each other, and this can lead to play-based experiences and interactions between students who would usually be unable to communicate yet. Often children will approach the teacher, wishing to say something to an EAL beginner student, like ‘I am making some invitations. What is your favorite colour?’.

For the teacher, speaker buttons allow them to explain the core concepts of a task to the students, across any subject. An example of this would be to explain the structure and purpose of a narrative text to an EAL beginner student using the translator. With the nature of the task embedded in the child’s mind, the teacher and student can discuss the work in detail as it develops. Thus, the progress, comprehension and aptitude of the child can be captured in a nuanced way. The use of speaker buttons is not limited to developing literacy skills, and can also be used when teaching difficult mathematical concepts requiring academic language.

[wpvideo MpdXl0UJ]Josh uses Google’s audio translate function to give class instruction in English and Chinese

When building reading skills, speaker buttons allow students to understand a text in greater detail, as the speaker button can immediately show the student the meaning of an unknown word and its context within the story. Upon completion, the teacher can ask for a summary of the story in the child’s home language, and see their full comprehension of the content.

Using Google Speaker buttons effectively does require patience and practice. It takes time for the children to learn to use them properly and they do not function as effectively in loud environments. Additionally, the programme cannot translate with 100% percent accuracy, and often requires some decoding on the teacher’s part, though students do quickly learn to recognize when something has not been properly translated. Also, not all languages are currently available, and some are better developed than others. However, based on our total observations and experiences, the benefits outweigh the costs substantially.

[wpvideo HbmchAcq]Google doesn’t always get it right first time, but after a few tries this Chinese pupil is able to effectively share his story with the class

Throughout this school year, the use of Google speaker buttons has been evolving to suit a range of purposes in our Year 1 classrooms. How frequently they are used, and in what context, fluctuates in line with the developmental and English growth of our year 1 pupils, as well as with the academic tasks they tackle each day. At the International School of the Hague, we strongly endorse the words of Maggie Grevelle, from her book Planning for bilingual learners-an inclusive curriculum:“learning should never be put on hold while we wait for a child to acquire a language”. Google speaker buttons have allowed us to make this learning vision a reality for our Year 1 children.

Josh is Y1 Teacher and Mother Tongue Lead and Mindy is Mother Tongue and Identity Language Leader at ISH. Follow them on Twitter at @ISH_EAL.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.