Teachers talking less than pupils: the value of small group instruction

I am in the closing weeks of my Indianapolis EAL project, and swimming in so much data that it is difficult to work out what my key findings will be. However, one thing has become a constant, and that is my observation of the value of small group instruction; not just for EAL learners but for all children that need space and time to grow their voice. Alongside this, I am further entrenched in my pre-project belief that a mainstay of great practice needs to be that teachers plan intentionally to say less, and for their pupils to say more. These elements of successful teaching are explicitly reflected in the Enduring Principles of Learning (see Letter #1 for an overview) as Joint Productive Activity and Instructional Conversation, and I will demonstrate how great teachers enact these during this letter.

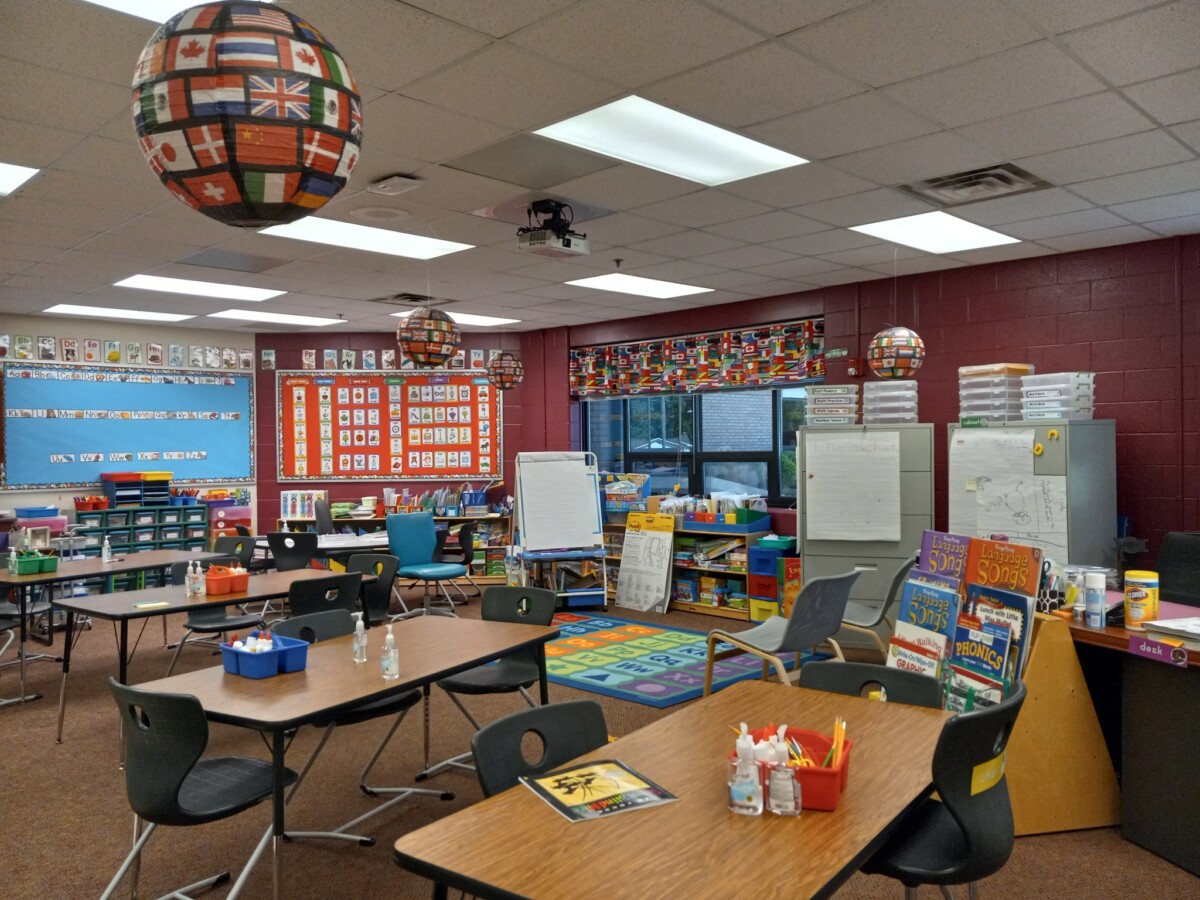

In this first example a first-grade teacher (children ag 6 -7) has a guided reading group of able readers, all of whom are African American. Bear in mind that she is teaching in a District which has below average test results when compared with like Districts, and that in this teachers’ school 98% of pupils are non-white. She has picked a book called ‘Everyone Says S..h..h..h..’ which is set in a movie theatre, and she starts by asking the group to work out what the book is about from the cover.

Teacher: So we’re going to start with a new book today and I picked this one very specially for everybody.

Child 1: They are at the movies.

Teacher: I thought I was going to have to explain that to you! How did you know that?

Child 1: Cause they’re eating popcorn.

Child 2: And there’s like red seats. Only movies have red seats.

Teacher: Only movies have red seats?

Child 3: It looked like a tent, first, when I first saw it.

Teacher – Why did you think that?

Child 3: Cause it was just all red.

Teacher: It’s kind of closed in looking isn’t it? Did you guys hear what (name) said?

(Several other children are sounding out the title together – ‘Everyone says……’)

Teacher: Let’s let (name) say one more time, what he said, because I thought this was really interesting.

Child 3: I thought like they were in a tent, a red tent it because it was like all red. And everyone is saying ‘shhh’. So then I knew. That’s when I thought that it’s the movies.

Teacher: So he said it kind of, if you look, see how they’re kind of close together, and it’s all red. He said it almost looks like it would look if you were inside a tent.

Child 4: Yeah. This says, everyone says, shhh.

Teacher – Oh my goodness, you are absolutely right! Now let’s look at this word, shh.

In this short transcript extract notice how the discourse is conversational rather than teacher-led question/answer. The teacher has cultivated a relationship with the children where they have agency to talk freely rather than waiting for her direction, and where they can strike up a conversation with the teacher that may or may not be with the rest of the group. The teacher and children work together, as peers, in joint productive activity.

Another aspect of this small group experience is that the teacher has chosen a book focussed on an activity which she knows all of the children have experienced. So, there is the chance of making connections beyond school, and with that the message that the children’s home experiences are valued. After this extract the teacher waited patiently while the children shared their movie experiences at some length with the group, and this meant that by the time she came to introducing the key vocabulary they were going to meet in the book, they had already aired some of these words in their conversation. This teachers’ practice, with children who had spent most of their Kindergarten year in virtual home-schooling, exemplifies instructional conversation where student talk is more than, and at a higher level than, teacher talk.

In this second example a second grade (age 7-8) teacher from the same school, is working with a group of English language learners of Band B/C proficiency who need support forming sentences for writing that is arising from a project on solids, liquids, and gasses. Before this guided writing activity, the children had been given questions to find answers using online resources connected with their reading scheme and were now ready to try and articulate their understanding of how solids, liquids and gases are different. The group are being given time for oral rehearsal before committing their thoughts to paper.

Teacher: So what’s the difference between a solid and a liquid?

Child 1: The solid…. it doesn’t… it does not change shape.

Teacher: Right. The solids don’t change shape. What happens if we pour milk out of a glass? What happens to it?

Child 1: It turns into a shape…. because liquids turn into a shape.

Teacher: Of wherever they are?

Child 1: Yes. Like juice… when you pour it into a cup …. it turns into the shape of the cup.

Teacher: It turns into the shape of the cup. Right. What if I poured juice on the table? What happens?

Child 1: It will splatter.

Teacher: Yeah. It goes flat like the table. …. So what about gasses? … What are gases?

Child 1: Gases?

Child 2: Helium

Teacher: Helium is a gas. How do you know helium is a gas?

Child 2: Because when you touch it …. it’s like a cloud ….. like the air we breathe too.

Teacher: So how are gases different than solids and liquids?

Child 1: Gases are different things because they are different from liquids…. Because liquids are something watery, and solids are something hard.

Teacher: So what about gases?

Child 2: Gases are something that are not hard or watery.

Teacher: Yeah, right. It’s not liquidy, it’s not hard, and it’s usually where? Where do we find gases?

Child 1: At the gas station.

Teacher: That’s a different kind of gas.

What I found impressive in this conversation was the tenacity with which the teacher kept questioning rather than telling, and the wait time she allowed while the children thought about what they wanted to say. She knew that the children should by this point have read and researched enough to answer her basic question – what are solids, liquids and gases? – and this gave her the confidence to keep waiting for the answers rather than giving them to the children.

Clearly there was still some work to do on their understanding of gases! I wondered how much of their lack of understanding would have been picked up by the teacher had she attempted this same activity with the whole class. Her intentional probing showed her not only what the children did know but, more importantly, what they did not know. Moreover, she found out that there was some confusion between their understanding of the term ‘gases’, because of the US word for petrol (gas) which is of course a liquid. This forensic checking on the children’s depth of understanding of content-specific vocabulary would have been absent in a whole class activity, with the potential that misconceptions would have been reinforced rather than countered.

When working with children from minoritised backgrounds – whether differences are linguistic, cultural or racial – it matters that teacher expectations are high and it matters that teachers give space to their children to grown their own voices. These two teachers, and the teacher in my Letter #2, are committed to this. They understand the need for intentionally dialogic practice and this comes from a desire to advocate for the needs of their children who are at risk from under-achievement unless all of their school teachers believe that they can excel rather than that they cannot. And yes, of course, they had also made sure that the rest of the class were engaged in meaningful activities which they could undertake independently; this level of independence hard won through careful training by their teachers from the beginning of the school term.

My observations of trainee teachers and their mentors in primary schools in England in recent years have shown me that there has been something of a mind-shift away from small group teaching, particularly group guided reading, and that pedagogy in England has perhaps become more whole-class oriented of late. I don’t know if this is universal, but I am finding that my observations chime with other teacher educators when I share my unease at this change with them. Where whole class teaching is handled well – I can think of excellent whole class teaching of reading fluency I have seen for example – then perhaps children with EAL, or children who just need to develop their voice in a school system that is not built for them, can thrive. But I wonder can discourse of the quality observed in the examples in this blog happen in a whole class lesson? Will the teacher intentionally plan to say less than the children when positioned as maestro at the front of the class? I look forward to talking more about these important features of practice with my research schools when I get home, and before then online as part of Voice 21’s Oracy October EAL panel on the October 19th.