Adapting to the realities of 21st century linguistic diversity among our school population can be a challenge. Bilingualism specialist Eowyn Crisfield describes how she and Jane Spiro, a colleague from Oxford Brookes University, explored how five schools in different parts of the world met this challenge, and could act as examples of what multilingual schooling could look like for us all.

Affecting school change is a fragile process. What can begin with enthusiasm and good intentions can often peter out in disappointment and unrealised aspirations. In trying to assist schools with making changes to their approaches to language diversity my colleague Jane Spiro of Oxford Brookes University and I noticed that the success of our involvement often rested on whether our guidance was embraced and its implementation supported, especially by school leaders. Disappointingly, this was not always the case.

Reflecting on these disappointments we realised that we wanted to better understand the mechanisms of school change. In particular, we wanted to learn from schools who were in the process of making significant change to their approach to languages. Jane and I knew of schools doing just this and so we embarked on the project that became our new book, Linguistic and Cultural Innovation in Schools: The Languages Challenge. In the book we tell the stories of five schools, each representing different countries and contexts, and all engaging in innovation around languages. We explored their linguistic backgrounds, what catalysed their changes, how they implemented change, what the impact has been, and what challenges remain to address. Ultimately, our research also evolved into tales of aspiration and success that we hope will help other schools to embrace their own languages challenge.

Over two years we gathered and compiled case studies by visiting the schools, observing teaching and learning, holding meetings with staff and parents, and engaging in informal conversations with members of the school community. We investigated the schools’ documentation around languages, including information from governments and accrediting bodies, so that we could understand the context of each school and its educational programme. We held in-depth interviews with school leaders and teachers. Our insider/outside approach allowed us to see the school and the process of change from different perspectives.

Our first school was a Waldorf School in Hawaii, involved in the revival of the Hawaiian language through education. The school faces challenges related to community and institutional support for the use of the Hawaiian language in education. Nonetheless, it is succeeding in creating an environment where Hawaiian is embraced by all, including non-native Hawaiian teachers and students.

Our second school was Europa School UK, a state maintained school in England providing a bilingual education for the local community. They are unique in the UK in providing a fully bilingual model of education in the state sector.

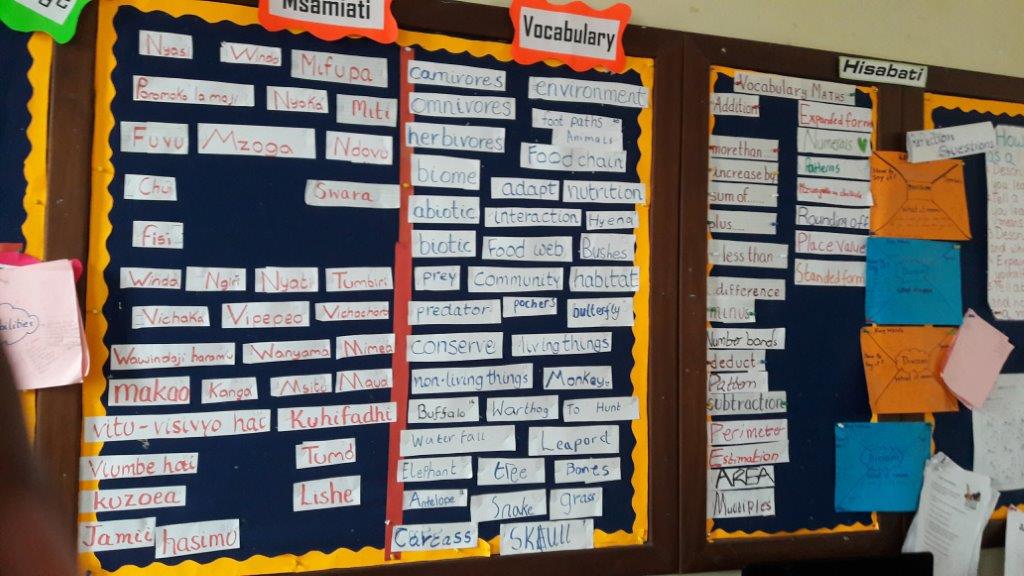

Our third school was The Aga Khan Academy, Mombasa, Kenya. It is on a journey from providing an elite, English-only education to providing bilingual Kiswahili-English education for local children. Their mission is to “square the local with the global” and allow students to access an internationally recognised education, while maintaining their roots in their own language and culture.

Our fourth school was the British School of Amsterdam. When we started working with them in 2009 they were on the verge of passing an “English-only” rule on the school grounds. Coming to realise this was unlikely to be best practice, they embarked on a journey to better understand and support their multilingual learners. They can be thought of now as a multilingual-friendly school with a British (monolingual) curriculum.

The final school we profiled was the German European School in Singapore. This school made the decision to move away from teaching only in English and German, to provide support for as many of the home languages of their pupils as possible.

What did we learn from our schools?

It is very difficult to distill into a paragraph what we learned from our schools, and indeed, Jane and I both had different experiences in the schools and different key take-away points. The three that seem most impactful and pervasive are: leadership, context, and teacher ownership. As one of the school leaders we worked with put it:

“The most important thing is to understand and believe in what you are doing. The rest (logistics, budget, planning, structures, etc.) can follow from there.”

It was clear from preparing narratives for all the schools that the importance of leadership in driving change cannot be underestimated. All of the schools we studied had strong leadership throughout the change process. Sometimes these followed classical structures, and sometimes leadership came from within. Changes in approach to languages is difficult, time-consuming and often expensive. Leaders who believe the change is right can provide the other elements needed for success.

Our second key take-away was the critical role of place and context in determining the right path for schools. Each of our schools reflected on their place, their people and their mission, to inform their change process. There is no one-size fits all when it comes to languages in schools, so while schools should look to others for inspiration, ultimately they must find their own way.

The final key take-away concerned teacher engagement and commitment. All of the decisions taken by school leaders made their teachers’ work more challenging in some ways. Teaching to the status quo is safe and comfortable; moving away from that comfort zone into new approaches and pedagogy requires teachers to become learners again. This not only requires taking on new knowledge and adapting practice, but also means deeply connecting with the change process in order to renew themselves as teachers.

Our main purpose in writing this book was to share the stories of our schools. We hope that these stories will inspire other schools to consider their approaches to multilingualism. What we gained from our research feels immeasurable. Both Jane and I came out of this process as better educators because of the many lessons our schools taught us along the way. We hope that other educators will find the stories of these schools as inspiring as we do.

Readers can get 20% off Eowyn and Jane’s book using the voucher here.

Follow Eowyn on Twitter @4bilingualism and view her website here.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.