Kamil Trzebiatowski, member of NALDIC’s executive committee and EAL Coordinator at a secondary school in Hull, describes some of the classroom approaches he uses for incorporating EAL learners’ home languages to support their learning in English across the curriculum.

The myth that EAL learners should only ever speak English and never their own language appears to still be persistent with many mainstream teachers despite bilingualism research indicating the precise opposite. Over the last year, in my own classroom, I have been incorporating the significant use of the first language (L1) for the teaching of a variety of subjects across the curriculum. In this blog post, I am sharing the kind of methods and approaches I have been trialling in my classroom with beginner EAL learners.

In embarking on this pedagogical adventure, I was inspired by the following four notions:

- Garcia and Wei’s Translanguaging – the idea that bilingual or multilingual learners do not simply switch between languages, but, rather, that their languages make up their complete language repertoire, resulting in original, complex and interrelated discursive practices (Garcia & Wei, 2014)

- Cummins’s Common Underlying Proficiency – particularly the notion that concepts, ideas and cognitive and linguistic awareness are shared and can be transferred from one language to another

- Thomas and Collier’s (1997) advising us that it is imperative that language, academic and cognitive skills need to develop through both L1 and L2 at all times to allow learners to succeed in school.

A CUNY-NYSIEB Guide for Educators is a 190-page document available for free online with hundreds of ideas of how to use translanguaging in elementary and high schools. It was one of the source of my inspiration for the activities in my classroom. If bilingualism and multilingualism are treated as one complete linguistic repertoire, it means we should endeavour to use two or more languages more or less simultaneously in our classroom – mixing up languages within one product or one lesson.

Understanding / reading

In many cases it should be possible, for instance, to purchase textbooks in the L1s of our EAL students covering topics being studied in English. For instance, I have used a Polish biology textbook covering the topic of photosynthesis, which my Polish pupils can read first before engaging with the same topic delivered in English in class.

Even simpler is finding short videos online introducing certain concepts to learners in L1. For instance, in a lesson on magnetism I conducted a couple of months ago, my Polish and Romanian pupils watched videos introducing them to the topic in their respective L1s (see here and here). You can quite imagine how the understanding of the concept of magnetism was immediately understandable to them, compared to trying to teach the concept through English.

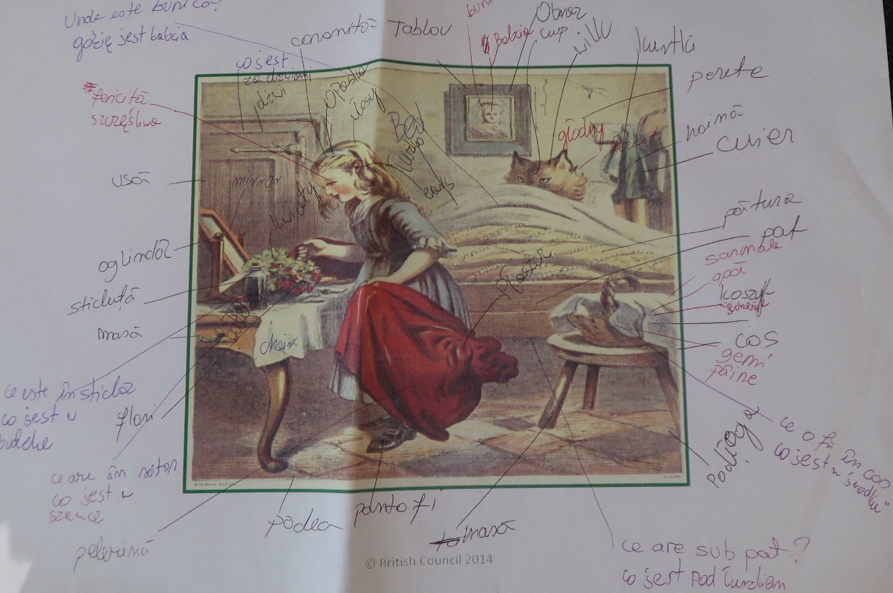

Another idea is to annotate English texts or images with ideas or insights in L1 first, then telling their partners through pair-share or reporting back to the teacher in English. Picture books such as Shaun Tan’s The Arrival– stories with pictures no text are perfect for annotation. There is of course no reason why children shouldn’t work together to annotate pictures in all of their languages together. The example below (based on an idea from EAL Nexus) shows how this looked in my classroom. Children moved from table to table, each adding their ideas to those of other groups. After this activity they wrote a short piece in English about their ideas.

Writing

Mixing languages for extended writing

For writing, consider two different approaches:

- learners write first in the first language and translate (perhaps as homework) into English

- learners complete differentiated work in English first and answer in the first language

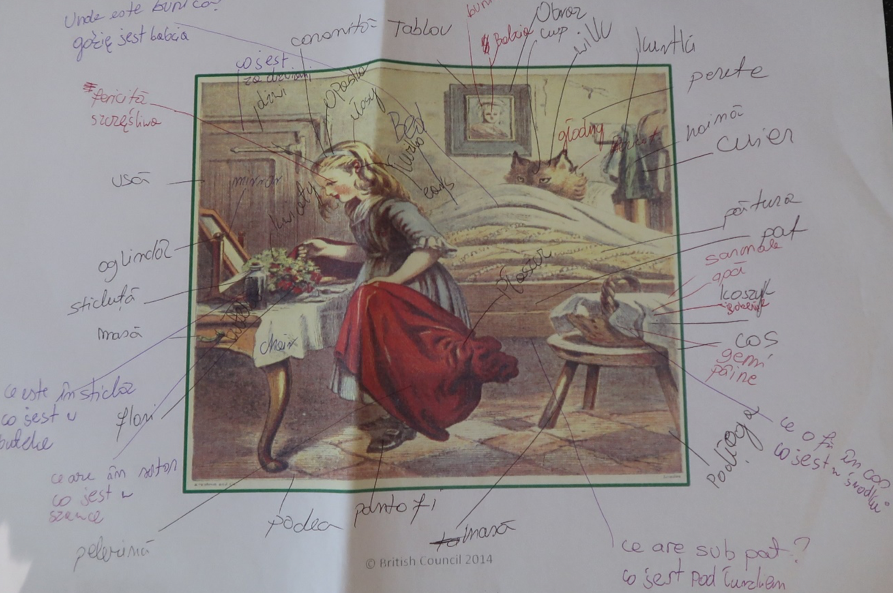

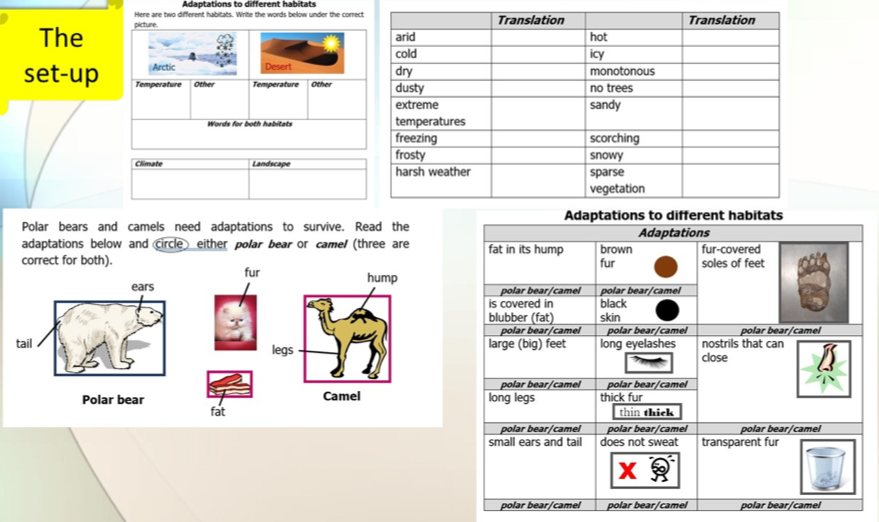

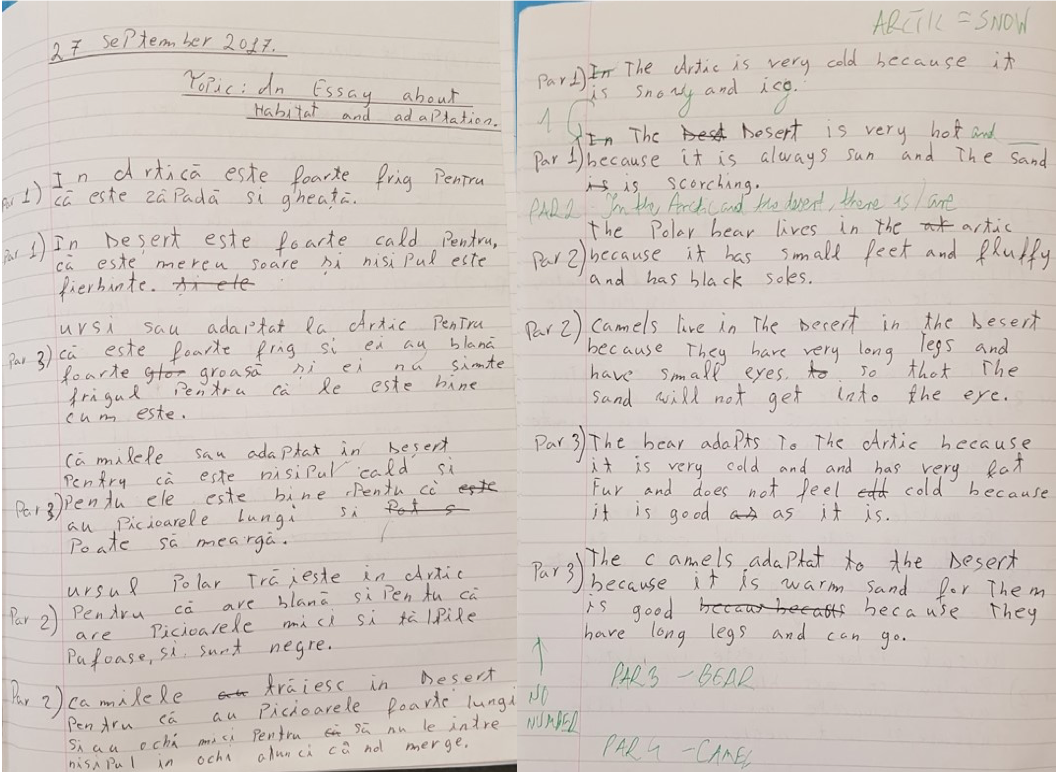

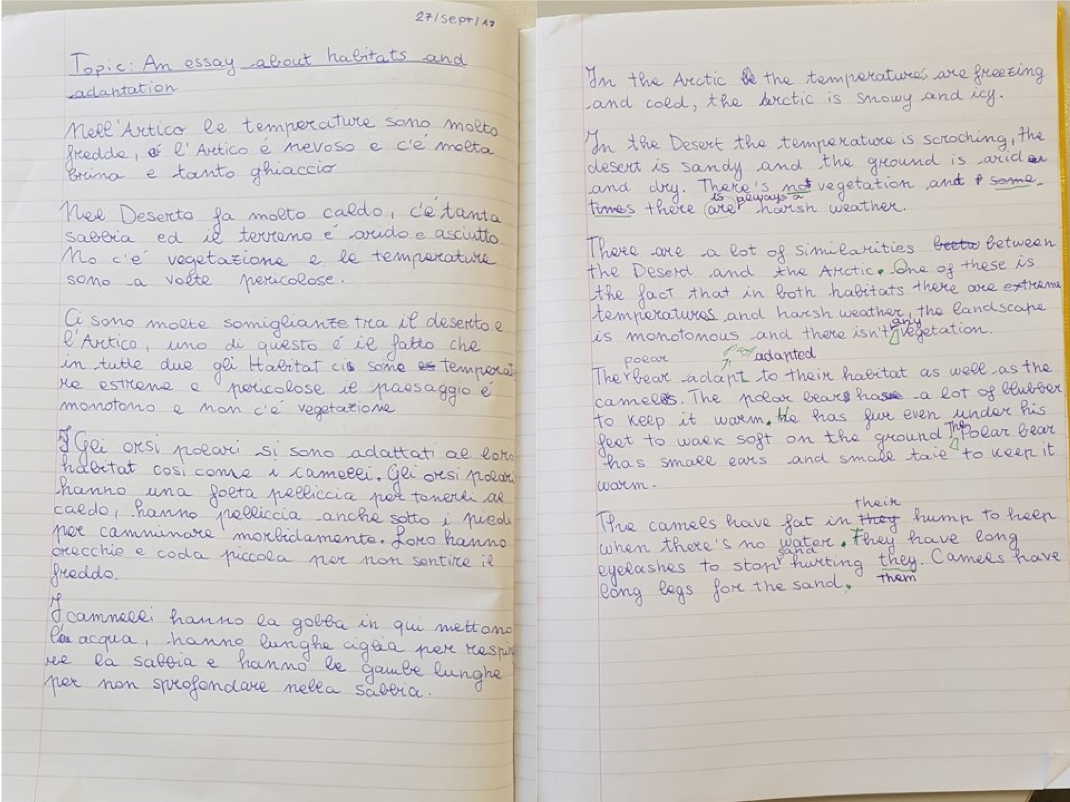

I used another EAL Nexus resource to put these ideas into practice in a science lesson on animal adaptations. First, the learners completed differentiated work in English. In the images below, you can see that this included the use of images to explain the keywords, labelling pictures, simple translation of terms from English to L1 and the use of substitution tables to scaffold writing in English.

Following this lesson, learners needed to answer the following five questions in writing using their L1.

- What are the conditions in the Arctic?

- What are the conditions in the desert?

- What are the similarities between the desert and the Arctic?

- How have polar bears adapted to their habitat?

- How have camels adapted to their habitat?

The learners then took home their L1 writing and translated into English for homework.

The difference in the quality of their Englishwriting – in terms of grammar, vocabulary and ability to communicate information – was astonishing by compared to similar activities using English only. Most of my students reported that not needing to deal with content and language simultaneously – i.e. not having to think of English grammar, structures and vocabulary whilsttackling their animal adaptations knowledge – put less of a strain on their working memory.

Following this task, I asked the learners to close their books, and asked them the same questions in English, but required them to answer them in their mother tongue. I might not speak Romanian or Lithuanian, but if the speed with which they were able to answer the questions – no notes, no books, just from memory – was impressive, and there was no question they had the knowledge. The beaming pride on their faces as they realised they could do it – was all I needed to know this approach is indeed successful.

Multilingual posters / products

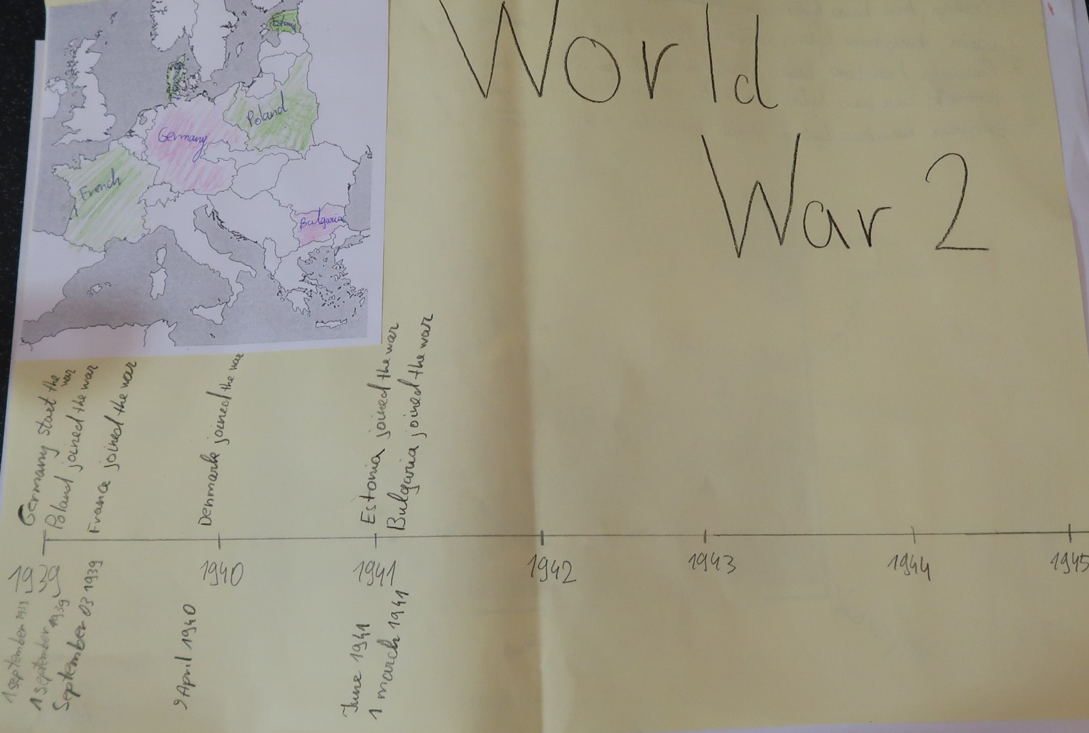

One final idea I will share is from a History lesson about World War 2. Here, the students were asked to create a timeline of when different countries joined the war (having done research online before). You can see one of their posters – it’s entirely in English.

But on the back of the poster the students wrote sentences using their timeline data – in their own languages. The very next lesson, they were to deliver a short presentation to their classmates: holding up their poster with the timeline in English visible to the audience whilst being able to read their sentences in L1, but now having to speak their sentences in English!

I hope that these examples help to inspire you to try some – and more! – of these types of approaches in your classroom. I find they help empower our learners, help take advantage of their prior knowledge and undoubtedly support the development of L2.

For more ideas for the EAL classroom, check out Kamil’s blog and follow him on Twitter @KTlangspec.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.