The EAL Journal blog publishes plain language summaries of EAL-related Master’s and doctoral research. In this post Katy Finch, doctoral researcher in the Division of Human Communication at the University of Manchester presents a summary of her Master’s dissertation on teachers’ experiences teaching modern foreign languages to linguistically diverse classes.

Why did you do the research?

For many teachers, pupils and parents alike, curriculum reform can bring with it numerous challenges. In 2014, along with quite sizeable changes to the English and Maths Primary National Curriculum, compulsory foreign language teaching for Key Stage 2 (children aged 7-11) was also thrown into the educational mix. Although initially overshadowed by changes to the core subjects, research prior to the inclusion of Modern Foreign Languages (MFL) suggested teachers felt underprepared and apprehensive about teaching French or Spanish to their classes (Barnes, 2006). This is understandable, considering a lack of societal and educational support for languages through the latter part of the 20th Century (Macaro, 2008). Many teachers just don’t know another language well enough to feel confident in teaching it.

As well as changes to the curriculum, the demographics of English schools have also continued to change; as migration and globalisation shape society. The linguistic diversity found in many schools is incredibly varied, with 20.6% of children in English primary schools now speaking a different language at home (DfE, 2017). So, with foreign languages now on the curriculum and one in five children speaking more than one language already, the assumption that most English schools are monolingual, English speaking environments can no longer be made.

So, as part of my Master’s programme and as a teacher working with learners of EAL and their parents, I was keen to find out how this interaction between multilingual learners and foreign language curriculum might manifest itself for teachers and pupils. Some teachers have expressed concern about how to approach the new languages syllabus, when so many of their pupils are still mastering English (Legg, 2013). Yet, such trepidation may not be necessary. Having a classroom of children with varied repertoires of language competence may not be a barrier in the MFL lesson, but in fact, a bonus.

What did you do?

Two years on from the introduction of primary MFL, I worked with six teachers in Greater Manchester to find out what their experiences had been delivering the foreign language curriculum to pupils with various home languages. Each teacher was interviewed for approximately one hour and asked about their thoughts and experiences of MFL in general and how it is being implemented in their school. They were also asked whether they perceive any differences in how children learning English as an Additional Language (EAL) respond to the curriculum compared with their monolingual, English-speaking classmates. These interviews were transcribed and analysed used Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis to find the common themes amongst the participants.

What did you find?

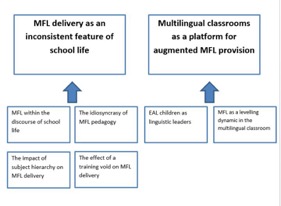

The overarching themes and subthemes found from the analysis are shown in Figure 1.

The findings suggest that MFL is an inconsistent feature in schools and that in an overloaded timetable, it is a subject that can easily be forgotten. A lack of formal assessment means it is often viewed as way down the hierarchy of priorities for staff and in many cases, this is exacerbated by a lack of confidence and competence in speaking another language. Teachers don’t have time to learn another language when they already feel over-burdened with their workload.

However, a glimmer of hope for the subject comes in the pupils’ response to language learning. Although Key Stage 2 teachers might recoil at the thought of songs, rhymes and pedagogy that generally involves a much noisier classroom than usual, the children appear to relish it. Furthermore, all the teachers involved in the project noted that the children learning EAL showed extra enthusiasm for the subject. It was found that MFL had a levelling effect in the classroom; if none of the class knows French or Spanish then everyone is starting from the beginning. The slower pace and interactive nature of the lessons also seems to suit children with lower levels of English fluency, as they can keep up with their peers more easily. In fact, most of the teachers suggested that their EAL pupils were the leaders in the foreign language classroom. With higher levels of confidence and participation, teachers feel that these pupils appear to have an advantage over their classmates.

What does it mean?

Where this reported advantage stems from seems to be the next logical question. Are the children more confident learning languages as they do it every day learning English? Do they have a more varied set of linguistic skills to draw upon when learning a new language; different experiences of syntax and phonology for example? Or is there something more cognitive going on? It may be that their prior experience of navigating the world in more than one language has improved their metalinguistic skills and therefore they can master a new language more efficiently. If the latter is the case, the MFL syllabus employed by teachers in multilingual settings may be modified to utilise these skills.

As part of my PhD project, I will be focussing on examining the specific metalinguistic skills of both monolingual children and children learning EAL, as they progress through their foreign language curriculum. I will also be looking at the pedagogy used by teachers to deliver MFL in multilingual classrooms and thinking about whether the language experience at home shapes the foreign language attainment of pupils at school.

So, rather than linguistic diversity being another challenge to overcome in the primary MFL classroom, it could be that the addition of foreign languages has a positive impact on a group of children whose linguistic profile is often seen as a deficit. Success and enthusiasm from pupils could also encourage teachers to persevere in the teaching of a new and often daunting subject.

This is a plain language summary of Katy’s Master’s dissertation, a version of which was published in the Language Learning Journal. View it here.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.