Kamil Trzebiatowski, EAL Coordinator at a secondary school in Hull and nationwide EAL consultant, describes how he uses substitution tables in the classroom to support language development across the curriculum.

In the past four years, one strategy that I – and indeed my students with EAL – found successful and empowering has been substitution tables. The strategy allows me to break the language demands for my students into manageable chunks, focus on an aspect of grammar and/or language specific to different curriculum areas, differentiate for different stages of second language acquisition (SLA) and promote independent learning. In this blog post, I show how I have used this approach in the past and how I have tweaked it to get the most out of the approach to benefit my learners.

The principle behind substitution tables is that their users are to pick one option from each column – left to right – to create several sentences. In my estimation, one table enabling you to write many sentences (ten or more) are more effective and fit for purpose than those leading to just 3 or 4 sentences. The creation of such tables can be laborious, particularly for novices, but the upshot would be your learners, in the lesson, spending at least a quarter of an hour working independently once you’ve done your work.

Very broadly, we can distinguish between two categories of substitution tables. The one on the left below focuses on the English language alone to the exclusion of any obvious links to school curriculum. There might be a place for it in the very early stages of SLA when your student has only just arrived into the country. Here, the linguistic choices available to the student are very narrow and limited – the teacher controls the language on offer very tightly; the focus of learning is here preference verbs (like, love, enjoy) followed by a verb + gerund (-ing). However, in the context of schools and EAL pedagogy, such tightly-controlled tables should be used very sparingly and, I’d suggest, only in the very early stages of learning a new language.

The table on the right, however, is an example of merging the teaching of both content (Geography) and language. It has a clear focus on phrases such as can grow / can’t grow and it’s too hot / it’s not enough, but the sentences also need to make logical and factual (geographical, you could say) sense. Thus we have a dual focus here:

- Language foci:

- modal verb can/can’t + bare infinitive

- structures too + adjective and not + adjective + enough

- Content foci:

- plants that can be grown in Jamaica and English in the winter and the summer

It is this second type of approach we want to pursue if we wish to help our learners learn English and through English at the same time. Below, I describe some of the approaches that can be taken to differentiate substitution tables even further. It seems self-explanatory, then, that we need to teach English and through English. This implies that teachers should avoid the easy temptation of only making the text accessible (or input comprehensible, if you will), but ensure that they focus on an aspect of language when producing substitution tables. In other words, inside our substitution tables there needs to be a question about language as the table below demonstrates.

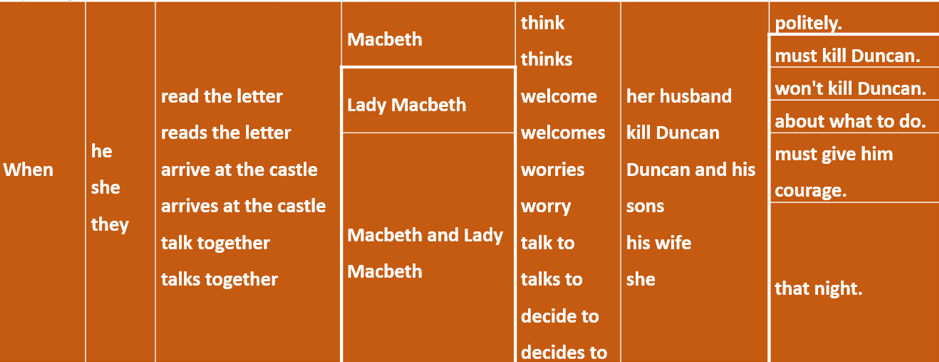

This table is adapted from the material the resources for Macbeth available at EAL Nexus. The original table is quite effective already, but I have added several options in the columns where the verbs are: the third column contains choices for read/reads, arrive/arrives and talk/talks and the fifth column asks learners to choose from think/thinks, welcome/welcomes, worries/worry, talk/talks and decide/decides. The grammar focus here is, of course, 3rd person singular verbs in the Present Simple tense. Adding the -s suffix or not thus becomes the language objective of the lesson. Not only, therefore, can we use this table to write a short summary of the story – which is what the original table was doing quite effectively – now, we also teach an element of grammar to our learners.

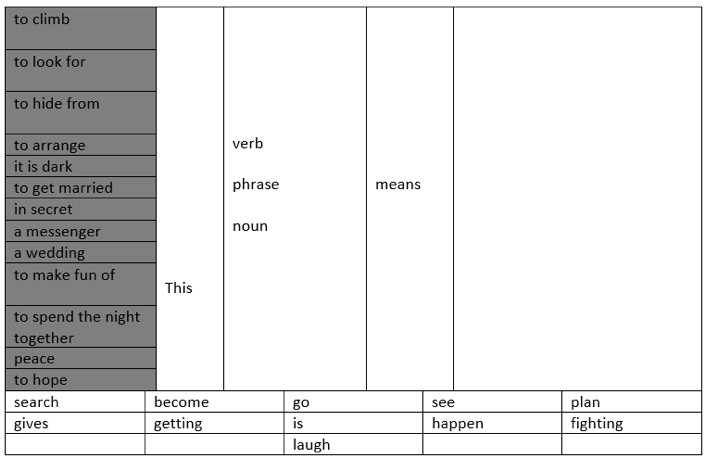

Many of us will likely know spot the error exercises from the EFL world which ask students to read a text and an error in every line. What if we make grammatical errors inside a substitution table on purpose to see if our students are going to fall for it (hopefully not!). See the example below: this was produced on the basis of one of the readings from the Racing to English CD resource.

You will quickly noticed that I made errors such as “didn’t goed” or “taked” on purpose to check the learners’ understanding of how to correctly use the Past Simple tense regular and irregular verbs in both the affirmative and the negative.

There is no reason why text and only text should be present in substitution tables. The following table, which I created for a lesson based on one of the resources available in The CLIL Resource Pack, has a similar focus on the Present Simple verb suffixes (as talking about facts in Science is delivered primarily through the same Present Simple tense). There was also an issue for a few of my students with using the pronoun they to refer to collective nouns, i.e. it = 1 kidney, but they = 2 kidneys, hence the it/they column. As you can see here, combining questions and answers in one substitution tables, I also replaced some of the words with images.

It could be argued that the images in the above table focus on the content of the lesson (scientific words to do with body organs) and not the actual English language. Clearly, it would be easy to replace the verbs with images rather than – or as well as – the technical scientific terminology. See below. The images relating to verbs are followed by the option to use -s or no suffix.

It is also perfectly possible to combine the substitution tables with other kinds of classic activities such as gap fills. The examples below, of my own creation, demonstrate how I have differentiated for three different levels within my group (low, middle, high, respectively) whilst teaching how to construct definitions.

The first (lowest) level provides the list of words to define and full content of the sentences, but the students need to choose the right combination of options to write them.

The next level, as you can see, provides a gap fill with selection of words to be used in those gaps below.

Finally, the top level is provided with the same words, but the phrases from the last column have been removed entirely; they have to provide the final part of the sentences themselves, but they do know that they will need to use the word list provided in those sentences.

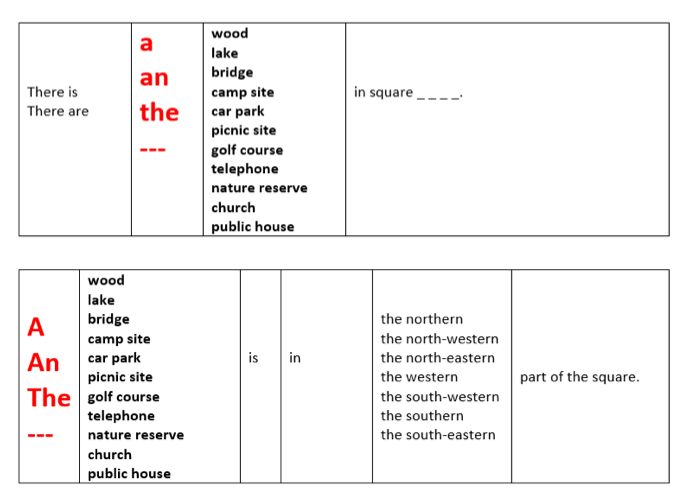

The potential that substitution tables have is truly great. Do keep in mind that we can use them as well as tools students can use for speaking, particularly if and when you want to promote exploratory talk in your classroom, which always requires structuring talk. Below is an example of how substitution tables can be used in a Geography lesson for a barrier game. In the activity, the task ahead of Student B is to find out from Student A where the different geographical features are so that they can draw them on their – mostly blank – map.

We provide the EAL learner(s) with a substitution table to facilitate the talk (here, the EAL learner is student A, providing information to an English native speaker). The English language grammar focus is the use of the articles a/an/the or lack thereof. The features vocabulary here (wood, bridge, church, etc.) does not actually include any word starting with a vowel, nor is there any reason to use There are…, but we are not going to tell them that and will monitor if they can use the full extent of their grammatical knowledge to make grammatically-sound sentences.

I would strongly suggest to anyone to take advantage of substitution tables when working with EAL learners. They allow for the practice (and repetition) of grammatical structures and vocabulary, promote independent learning and are open to virtually endless adaptation for the contexts and the learners with whom you work.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.