The EAL Journal blog publishes plain language summaries of EAL-related Masters and Doctoral research. In this post Hamish Chalmers, doctoral researcher at Oxford Brookes University, presents a summary of his Masters research into the effects of a translanguaging-inspired approach to teaching in linguistically diverse classrooms.

If you would like to write a plain language summary of your postgraduate research we want to hear from you. Check out the instructions to authors here.

Why I did this study

It is thought of as good practice for teachers in English schools to provide children who use a language other than English at home with opportunities to use their home language in class. People think that doing so will help these multilingual learners’ to learn English and support their learning through English. Research in schools that use both the home language and English (bilingual schools) tells us that sustained development of multilingual learners’ home language alongside English results in better educational outcomes. Compared with peers in schools where teaching and learning is conducted in English only (monolingual schools), multilingual learners in bilingual schools tend to develop better command of both English and their home language, and achieve better results in tests of subject knowledge.

The advantages associated with bilingual schools have led some to suggest that teachers in monolingual schools should incorporate home languages into their usual teaching. A popular jargon term for this kind of approach is translanguaging. Some people say that translanguaging approaches to teaching help multilingual learners to do better in school. A translanguaging approach includes, for example, creating dual language vocabulary lists with Google Translate; asking learners to draft a story in their home language then write it up in English; and having bilingual teachers discuss the contents of an English language text with multilingual learners in their home language. Some people say that these strategies can be used in classrooms where children speak many different home languages as well as in classrooms where everyone speaks the same home language.

I looked for reports of research that evaluated these kinds of strategy. I wanted to find research that described translanguaging strategies in sufficient detail for me to be able to replicate them in my classroom. I also wanted to find research that gave a clear indication of the effects of these strategies on outcomes that matter to me, my pupils, and their parents, such as English language development. I found a vanishingly small amount of research that met these criteria. I also wanted to find translanguaging research that had been conducted in schools like the ones I taught in; schools with lots of different home languages. I found no research of this kind.

This is not very helpful for the many millions of teachers working in similar circumstances to me. Teachers have finite resources of time, energy and money. Investment in new approaches such as translanguaging must be informed by evidence that this investment is worthwhile. The motivation for my research was to help to address the lack of relevant evidence and so help teachers make informed decisions about teaching strategies.

What I did

To help address the gap in the relevant evidence I had found, I designed a ‘translanguaging-inspired’ strategy for supporting Literacy through use of multilingual learners’ home languages. I compared the effects of this strategy with a similar strategy using only English.

I recruited thirty-six multilingual learners in Years 1 and 2 at a primary school in Oxford to take part in the study. Between them they spoke twelve different home languages and used English with varying degrees of proficiency.

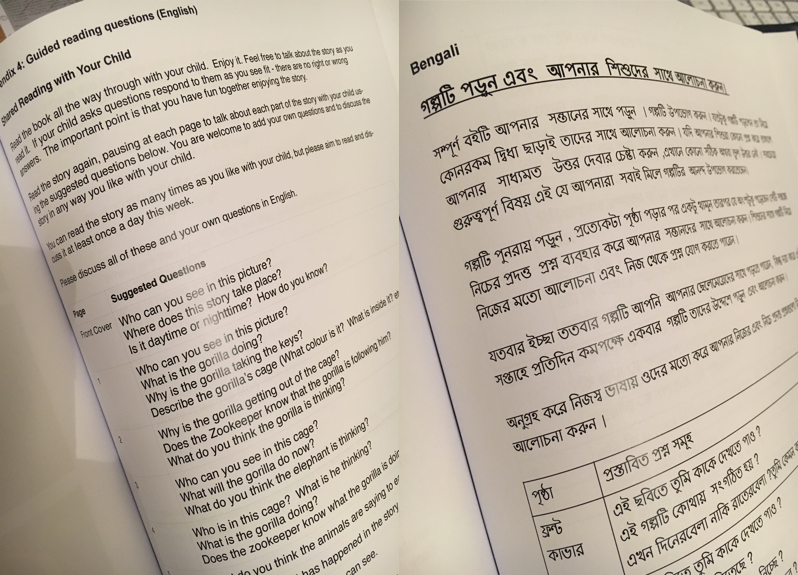

My strategy was based on the suggestion that discussing the contents of an English text in the home language helps children when they work on that text later in English. Because – unsurprisingly – none of the adults at the school could speak all twelve languages represented among the children, the strategy could not be carried out there. Instead, I asked parents to take on the role of the teacher, and to help their children discuss the contents of a text at home. I gave each family a copy of a picture book with very few words and a clear narrative structure. I also gave them a set of questions designed to guide their discussion around the story. There were 13 versions of these questions, an English version and translations into the 12 different home languages.

Children were divided into two groups by pulling names out of a hat. One group was called the English Only group and the other was called the Home Language group. Children in the English Only group were given the set of guiding questions in English. Children in the Home Language group had the appropriate translated version of the questions. Parents were asked to read and discuss the story with their child in the language allocated to them (English or their home language) on as many occasions as they could during one week.

At the end of the week, the children independently wrote re-tellings of the story in class. I assessed these written re-tellings using the school’s usual literacy writing assessment scale and a popular English language assessment scale. Then I compared the average scores between the two groups of children.

What I found

On average, children in both groups scored the same on these assessments. Neither the Home Language group nor the English Only group appeared to have benefited, or been disadvantaged, by either approach.

What it means

My study attempted to address uncertainty about whether translanguaging approaches to teaching multilingual learners are useful. I described a translanguaging-inspired strategy in detail, then assessed the effects this strategy on outcomes that are important to teachers, their students, and their parents. My study did not detect any advantage (or disadvantage) to using the home language in this way, compared to using only English.

It is tempting to interpret these findings to mean that teachers should be free to choose whichever of the two approaches to parent-supported reading (home language or English only) they feel is most appropriate. In such cases, reasons other than any effect on English literacy may well inform teachers’ decisions. For example, one of the concerns often voiced by parents who want to use their home language with their children at home is that doing so might negatively effect their children’s learning of English. My study adds to the existing body of evidence suggesting that this concern is unwarranted. My findings also imply that, in the absence of research that robustly assesses the kind of intervention I have described here, the resources used to implement it may be more effectively used for alternative strategies for which there is strong support from research conducted in classrooms.

Hamish’s dissertation was shortlisted for the 2014 BERA Masters’ Dissertation Award and was a finalist for the British Council ELT Masters Award. The British Council subsequently published his dissertation in full here.

EALJournal.org is a publication of NALDIC, the subject association for EAL. Visit www.naldic.org.uk to become a member.