Teacher Laura Barter and her supervisor, Dr Beth Marley, show how Colourful Semantics helped Year 1 bilingual pupils improve their writing

How can we help young bilingual learners feel confident in their writing? At Whitehall Nursery and Infant Academy, we started with sentence structure, and Colourful Semantics (CS) made all the difference. Developed originally to support children with speech and language impairments (Bryan, 1997), CS uses colour-coded visual cues to build sentence structure, which we adapted with encouraging results.

How can we help young bilingual learners feel confident in their writing? At Whitehall Nursery and Infant Academy, we started with sentence structure, and Colourful Semantics (CS) made all the difference. Developed originally to support children with speech and language impairments (Bryan, 1997), CS uses colour-coded visual cues to build sentence structure, which we adapted with encouraging results.

Why Colourful Semantics?

Colourful Semantics supports understanding of grammar by colour coding thematic roles in sentences (e.g. ‘Who?’ is orange, ‘What doing?’ is yellow and ‘What?’ is green) and helps users to identify the syntactic forms of sentences. It focuses on the development of syntax through a semantic route (Bryan, 1997). Although originally developed as an intervention to support children with speech and language impairments, teachers at Whitehall have been using CS to support their EAL learners with positive outcomes. I (Laura) wanted to explore this further and set about designing a progressive intervention as part of my Master’s research project at the University of Birmingham. The use of CS to target common grammatical concerns, such as article misuse and word order errors, has proved fun and effective!

Designing the Intervention

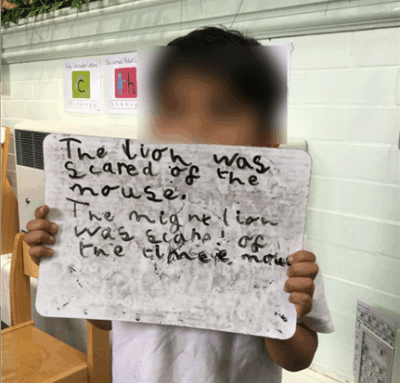

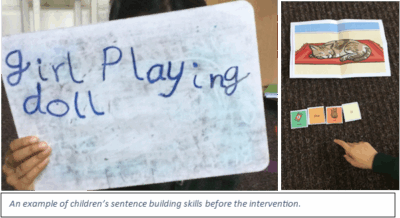

Using the Proficiency in English (PiE) scale (Demie, 2018), we identified six Year 1 students with limited English proficiency who demonstrated persistent grammatical errors in their writing. These students attended a weekly after-school club for seven weeks, where they built sentences using CS cards, orally rehearsed them, and then wrote them down.

The intervention was structured to encourage students in the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978), where support was provided but gradually reduced. We began with the basic CS framework (Who? What doing? What?) and progressed to children ordering articles and auxiliary verbs with increasing independence.

Unexpected Outcomes: Building Confidence and Community

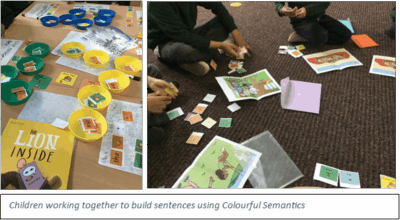

You would not be wrong in assuming that an after-school club focusing on writing skills may not be the most entertaining thing for a Year 1 child. That’s what we thought! Before starting the intervention, I was concerned that engagement would be a challenge and that the 45-minute session would be a chore for all of us involved. It turns out, Colourful Semantics was just what we needed! Week after week, the students would eagerly wait to come into the class after school, quickly setting up their resources ready to get on with the activities of the day. They completed the activities with enthusiasm and were eager to build more and more sentences. The classroom was filled with talk and laughter—but interestingly, much of it was in Punjabi!

The intervention provided a safe space for their home language to flourish as all participants shared Punjabi as a first language and used it to discuss their ideas. Encouraging and enabling their home language had a positive impact on their structuring of sentences in English. This was noticed by a Punjabi-speaking colleague who observed the sessions and reported that children were not only translating CS sentences into their home language, but also playfully adapting them (e.g. placing “the girl on the swing” onto “a tree,” “a cloud,” and even “a ball”). This spontaneous sentence play demonstrated the confidence and creativity that the intervention created.

Measuring Progress

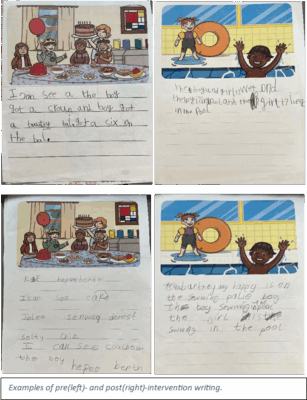

Not only did they have fun and build connections, but the children’s sentence structure in their writing definitely improved. After the 6-week intervention, there was a 27.7% reduction in mean grammatical errors and a 100% decrease in both article omissions and misuse. In addition, word order errors, a common difficulty among EAL learners (Potgieter & Conradie, 2013), were not observed in the post-intervention writing. Students’ PiE rankings improved and their writing became more complex, using adjectives and conjunctions with greater confidence. Pupils were observed to orally rehearse their sentences more fluently and check for grammatical accuracy themselves. We were really pleased to see this as an indicator of growing independence.

Looking Ahead

When I shared my findings with the teaching staff at Whitehall, they were excited to see a clearer framework for supporting grammar development in bilingual learners and planned to use the intervention design to assess what their own students needed to improve. Within my year group, we have incorporated the intervention design into our English writing planning and have seen CS help our bilingual students write more cohesively and independently. And yes, we will continue to run after-school clubs to help bilingual children develop language use and writing skills with their friends.

References

Bryan, A. (1997). Colourful semantics: Thematic role therapy. In: S. Chiat, J. Law & J. Marshall (Eds.) Language disorders in children and adults: Psycholinguistic approaches to therapy. London: Whurr. (143–161).

Potgieter, A. P. and Conradie, S. (2013). Explicit grammar teaching in EAL classrooms: Suggestions from isiXhosa speakers’ L2 data. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 31(1), 111-127.

Demie, F. (2018) English language proficiency and attainment of EAL (English as a second language) pupils in England, Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(7), 641-653.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Find out more about multilingualism

Find out more about multilingualism

- Join one of our Regional or Special Interest Groups

- Attend the next NALDIC annual conference in November

- Do you have a story to share? Write a post for the NALDIC blog